The Warehouse of Forgotten Objects Offers Memories Wholesale / Museo Folklórico Don Tomás Morel

Nicolás Dumit Estévez

The person who initially set out to design a chart that included photographs of the most notable “eccentrics" of the city of Santiago de los Treinta Caballeros did not forget to include Miss Universo. Founded in 1962 by Don Tomás Morel with the support of a group of friends, the interior of the museum that bears his name presents itself to the visitor as a stage always under construction. This is a space where an unusual hodgepodge of archaeological pieces, objects of historical value, artifacts, and trinkets coexist in the most perfect harmony—all of them brought together under the rusty zinc roof that crown the Victorian building. Black and white photographs of characters such as Abejón de Coco, Arcadio the preacher, Memé, and Puna gift visitors with an insight into a city that during the last decades has been attempting to reclaim its historic downtown as suburban development expands. That was the old Santiago where Puna used to run through town, from time to time, as God brought her into this world, naked, and as we would say in Dominican Republic, en pelotas. Her portrait, together with that of a cohort of our most recognizable “crazies,” find a place in this uncategorizable archive where they are simply classified as folklore.

Legendary among her fellow citizens, Miss Universo, was the woman who managed to create for herself the image of a beauty queen with sunglasses à la Sophia Loren: a big afro, hot pants, a low-cut top, and layers after layers of heave makeup. She survives her early departure from this planet in a text written by Don Tomás himself. María, on the other hand, was the stoic visionary who, dressed in a blood-red garment, climbed perhaps more than once to the very top of the city’s Monumento a Los Héroes de la la Restauración. Picture the Eifel Tower in Paris or the Statue of Liberty in New York City. The pretext behind María’s urban alpinism was said to be that of allowing her to have direct conversations with the Almighty. The collection honors her in a piece of writing that mentions her conferences with the thereafter. Under the title Evolution of Dementia, Evolution of Demencia, is how the Museo Folklórico groups these individuals whom Don Tomás argued, the village incorporated socially to counteract boredom. A subtitle expanding on the subject of acceptance is that of: Dementia-Environment Relationship. The author’s thesis elaborates on the reality that characterized the “mentally ill” person of the village, the countryside, and the city. Don Tomás speaks of the anonymity of the urban “madman” or person nowadays, hence referencing the physical and social transformation that the city has been undergoing. At the moment of updating this essay, written maybe two decades ago, Santiago seems to have embarked on an identity search whereas the overall rethinking of the city, in my opinion, appears to copy models like those of the abandonment of downtowns in the US, which are now being reclaimed. But in Santiago we have the recent advent of gated communities that speak tacitly of cultural, social, racial, and class segregation.

Santiago quien te vio y quien te ve…, Santiago, they who saw you before and see you now..., is a popular phrase in the north of the island, alluding to progress. This speaks to me of the same wrecking ball that has turned so many Caribbean Victorian houses into parking lots, and which renders invisible people like Puna, María, or Miss Universo. This is a city of Airbnb rentals and hideaways like La Quinta de Pontezuela, the gated community built to emulated the white picket fenced US house, and where the wealthy can turn an eye away from Dominican disparities. In the inclusive Museo Folklórico Don Tomás Morel, the room dedicated to Dominican popular religiosity is overcrowded with the saints that make up the Catholic pantheon. These holy beings have been rightfully appropriated by the enslaved from Africa brought to the island, and as a way of safeguarding the religious heritage of cultures that the colonizers tried to silence unsuccessfully. At the center of the altar that occupies an entire wall in what may have been before a bedroom, the delicate white hands of Metrésilí in a print playfully manipulate several yards of gold chains. La Metresa is the coquettish Vodoun loa who likes to receives gifts of elaborate cakes and fancy perfumes, and who tends to flirt with the men. I call her dearly, La Dominicanyork, thus pointing and at the same time imploding gaudy stereotypes of those of us Dominicans living in New York City. La Metresa conceals herself under the image of the Catholic Mater Dolorosa, whose baroque chromolithograph at Museo Folklórico talks of the predominant aesthetic enveloping her. Without reservation, the excess of objects on the altar establishes the parameters that the other spaces within the casona, the big house, must follow, introducing the visitor once and for all to the horror vacui that prevails throughout the whole building.

Like his father, Don Tomás, Tomasito Morel, who came to inherit the Museo Folklórico, organizes mask and poster contests during carnival. In this way, the Museo continues to attracts contributions from established artists as well as self-taught individuals, which are later added to the collection. However, it is the donations of objects from everyday visitors and residents of Santiago that give the space its function as the town's treasure chest or attic. As Santiago succumbs to modernity and the lures of US imperial economics and aesthetics, the museum receives a regular infusion of the objects the city discards, serving to expand its archives and dutifully cramming any available crevice. Bear in mind that in this context, there is no storage or rotation of items, like in most museums, and that all the Museo gets is what you see. So this becomes a site to gauge the city hosting it, and where a great deal of the material culture of Santiago escapes the landfills and goes to live. As Santiago purges itself of its past, its contents are deposited, in a disorderly dream-like fashion, in what was once Don Tomás's residence, the Museo. For this reason, the collection assumes the function of a city-wide closet, while simultaneously relieving the city of the burden of having to remember everything, that is, the heavy weight of memory. The chaotic nature of the collection, much like dreams and memories allow for the most surprising juxtapositions. A photograph of dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo, for example, coexists just inches away from one of the Mirabal sisters, the three siblings who fought the regime at the cost of their lives. Only one survived. Is this a practical strategy for the Museo to make an efficient use of its limited space, knowingly or not, unraveling political and ideological clashes? In the photograph, Trujillo smiles faintly, creepily, his cheeks caked with pink compact powder, clearly revealing the Blackness he attempts to hide.

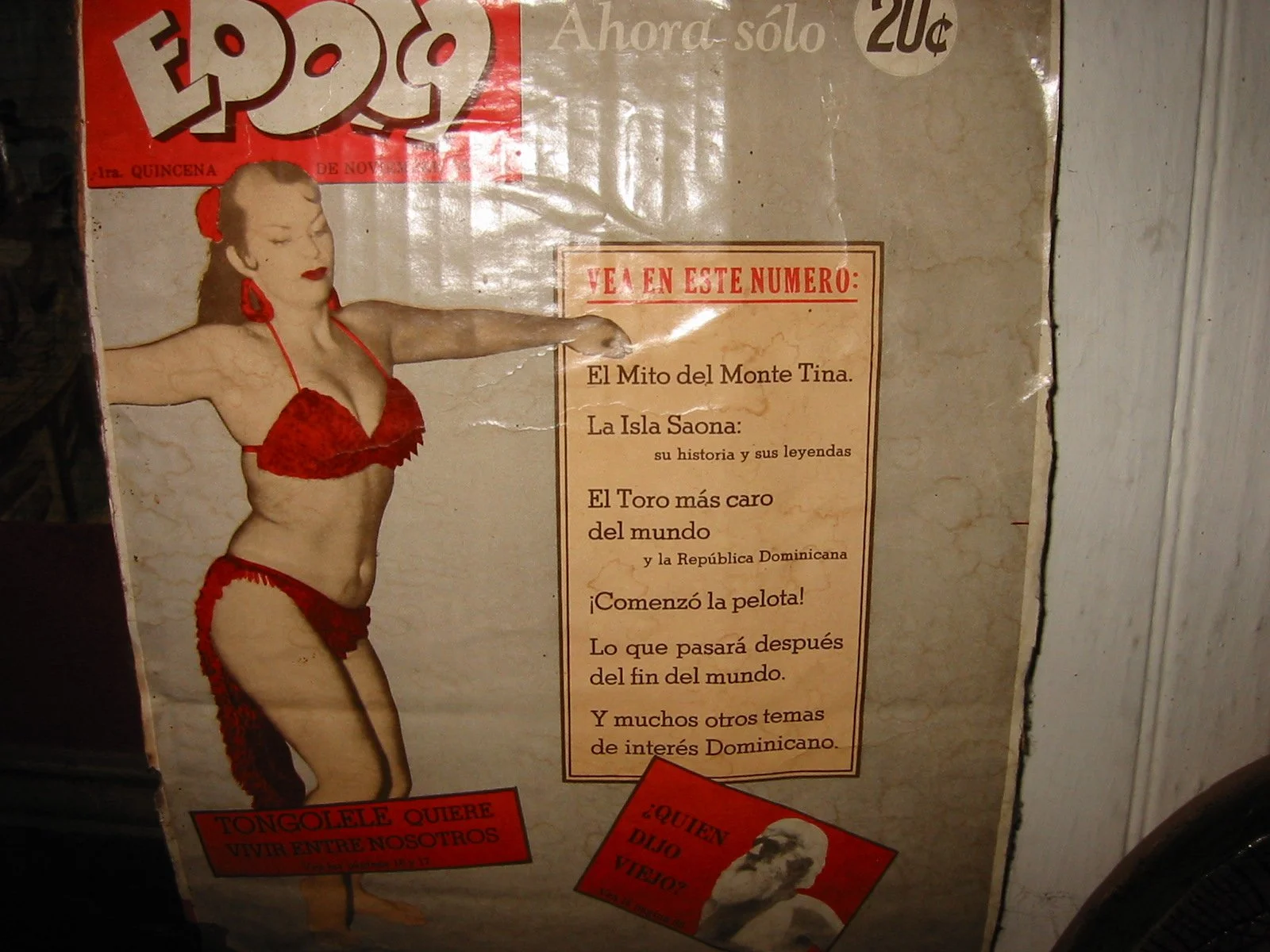

The receptiveness that the Museo seems to attribute to folklore threatens to absorb everything into it, to swallow it, much like the syncretic nature of Dominican culture at large. Everything goes and there is a way to make it our own. Take as an example the Dominican Vodoun altar with its Catholic saints, porcelain Buddhas, plaster “Taíno” figurines, to name a few. This might be why Tongolele, the burlesque vedette from Spokane, Washington, and Indio Araucano, the Mapuche poet and singer from Chile, share a spot with a group of Taíno relics. Tongolele wants to live among us, reads a yellowed publication that shows the Latinized showgirl wearing a bikini, doing everything she can to conceal the cellulite of her thighs while simultaneously trying to accentuate her voluptuous curves. Sporting her distinctive white skunk-like mechón, Tongolele is not alone: discarded clay pots, a plastic doll, a dragon mask, a kite, an unusually large key, and a rag doll made by Doña Ercilia Pepín, a well-respected former teacher in town, keep the dancer company. Tongolele and Indio Araucano stand guard over the box where visitors' donations go. On the front of this box, the phrase Help us maintain the Museum, Ayúdenos a apoyar el Museo, is written around a slot decorated with the paining of an open mouth that awaits to be fed some creased Dominican Pesos. At Museo Folklórico Don Tomás Morel Museum, there's room for everything, especially that at risk of being forgotten or disappearing; including the Museo itself.

Postscript: In 2013, I returned to Santiago from my home in the Bronx to enact an eight-hour ritual performance at Museo Folklórico Don Tomás Morel. To my dismay, the collection was reduced to a miniscule pile of what it was. The narrative goes that the Museo’s collections were thrown into the streets and destroyed by one of its former employees who was going through a mental breakdown. I am glad that I still preserve in the Bronx a couple of the publications that Don Tomás published with his own printing press, once housed in the premises of the Museo. Santiago, quien te vio y a quien se le dificulta reconocerte, Santiago those who saw you and can hardly recognize you. It may be that we both have slowly become strangers.

The Warehouse of Forgotten Objects Offers Memories Wholesale / Museo Folklórico Don Tomás Morel © Nicolás Dumit Estévez

To return to Incantations main menu, click HERE