Quintín Rivera Toro

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles: Quintín, I recall meeting you at Transart Institute many summers ago, in Berlin, in one of the upcycled industrial buildings in town. I can feel the cool breeze of the summer there and the joy that it was for me to be in Berlin then. What have been transpiring for you since that time?

Quintín Rivera Toro: Querido Nicolás…what a wonderful way to begin this process, recalling this amazing past, making me live it twice, thank you. I have transpired so much. I transpire right now as I write. Since the Summer of 2010 I have matured into an old young man; I have become a “doctor” in art matters and have been sober for a few years now. I am a proud father of a future declonializing revolutionary name Violeta and I make it my purpose in life to stand strong against all forms of oppression which I can affect, through art mainly, but also through teaching and being.

NDEREO: Puerto Rico has been central to your praxis as a creative. It has been key to me, perhaps in a less direct way, but still. While living in New York City for 30 plus years, Nuyoricans, New-York Ricans and other combinations of Ricans has kindly mentored me, guided me and open doors for me. I am grateful. I am wondering if there are strong traditions in your cultures about mentoring, community engagements, and supporting one another? I do not mean to generalize and yet some cultures can be more individualistic-oriented than others.

QRT: I love the question about mentorship. As a young poet (artist) I looked eagerly for one. I couldn’t find any. I guess I was enamored by the idea of becoming someone's apprentice, but it seems such practices were displaced by capitalistic thought. All I could find were jobs, where the successful artists would stand in as a proxy. Nevertheless, I have found countless professors, such as yourself, who for short periods of time, usually a semester, would serve as guides and inspiration. I remember writing in an opinion column that mentors were figures of a distant past now, and that we should give up on finding them. It seems I followed my own advice. On the other hand, I have never mentored anyone myself, so there, I guess it's an even score, even if a somewhat sad fact. Puerto Rico continues to be a central aspect of my praxis, because there is a perennial urgency here. We live under many forms of oppression in this country and it is very confusing how to resolve it. In the meantime, we make art about it, we hold the torch and our faith until the revolution is irresistible.

NDEREO: A subject that is rarely touched, I feel, in conversations about Puerto Rico is that of racism. I experienced some of this in the Island. People would think that I was Puerto Rican, because many of them correlated Dominicans with dark skin. Those who saw me as Puerto Rican thought that I should be grateful not to be associated with Dominicans. I was enraged by this.

QRT: It is a very interesting experience you relate here, one that perhaps I could relate to in some ways. Having been born into as many privileges as there seem to exist (being born into a white body, constructed and happy with my heterosexuality, continuously educated; and being the son of a poor man who became the perfect example of a wealthy, workaholic, baby boomer), I can’t really say I have been the target of racism at all. Nevertheless, my grandmother is a dark-skinned Dominican born person, African heritage manifests directly in my genetic pool of family members, etc.; yet I was born white. I therefore relate ideologically with gender and race justice, but can’t really feel the ownership of such fights. I have recently learned that my place as an ally is to quietly stand to the side and allow for my sisters and brothers and chosen families to be supported through the best of my intentions, through my artistic, social and political work.

NDEREO: Internally, a Black Puerto Rican friend of mine is usually stopped at the San Juan airport. They think she is a Dominican trying to enter the Island with false documents. You and I have light skin, and have derived privileges from that, and we both know that we are a minority in our adored Caribbean. How would you say is Blackness and its tremendous contributions to who we are as Caribeñes being given the space it deserves in Puerto Rican society?

QRT: This is a very complex question, and it feels that in the year 2023, most non-white individuals would object to my slightest opinion; nevertheless I do have a point of view, perhaps many. The answer is, generally speaking: not yet. I will answer that within myself, I give the African heritage that manifests in my body, in my culture (dance and music), in my history, in my friends and family, a place of utmost urgency, for it to be corrected and compensated; and it feels like a point of inflection. I believe things are changing and that the artworld has a lot to do with this. The conscientious effort to support the black, brown, latino, LGBTTQIA+, et al, communities through art prizes, fellowships, residencies, etc. has reshaped the landscape. I am aware of this in many ways and it feels correct. Alabanza a las manos que trabajan la nueva patria, wrote Juan Antonio Corretjer.

NDEREO: I know that can talk with you with an open and honest heart. No decorations. How does it feel somatically to be part of a colony? Dominican Republic, unlike Puerto Rico is a seemingly independent country, and it still operates under the U.S. Colonial shadow and Europe’s new neocolonial rule. Do you have any practices for engaging in decolonization at a spiritual level?

QRT: No one had ever asked me this question, thank you. Somatically, it feels embarrassing. I feel like a loser, like I lost, we lost, we continue to lose. It feels depressing and it lowers my existential self-esteem. The general historic and political discourse, and my mind tell me, that I come from a small country, with lost efforts for independence and that anyone can walk all over our political struggle with the entitlement of an idiotic bully. I have lived it so many times: “oh, but you are not even a country.” I make it my life’s purpose to decolonize Borikén. It is my existential commitment to myself, my daughter and my history. Spirituality is something I have only been really close to either during hardship and through art making to a lesser extent. Yet as I become older, I realize the need for a spiritual dimension in my life, so I guess I’ll say…coming soon. If currently, decolonizing my brain from false ideas about our own history is a main priority, decolonizing my heart and spirit will certainly follow.

NDEREO: I think of so many Caribbean comrades and of a Caribbean solidarity movement, at least within the creative field. Jean Ulrick Desért has generated a Creative Caribbean Community and Diaspora passport. The Salon has a copy of it in its archive. So complex. I mean the Caribbean, with all of its colonial connections and the severing(s) to be made. Where are you in this conversation about Caribeñidad?

QRT: I have a basic argument regarding the fundamental processes for the unification of the Caribbean thought and efforts. First, there is language. All of the Caribbean speaks in different languages due to the cruel reality of having been colonized by the French, English, Danish, Spanish and, more recently, north american exploiters. Therefore, in a general, basic sense, we can’t communicate. Forget Babel, look at the Caribbean. Second, as romantic as it all may sound to develop a solidarity movement, for this, people need to meet, congregate, exchange and commerce together. Our air ways and water ways are completely restricted by the military powers that be. We cannot visit our own fellow islanders freely, we cannot commerce freely we are neoliberal slaves to north american capitalist interests. A sad and harsh truth. The place where the conversation ends and we drink up to forget.

NDEREO: Tell me about your work about revolution?

QRT: Thank you, Nicolás, for asking me this. It is probably ask bold and rebellious a work as I have ever made. The New International Antillian Declaration, as I would translate its long name, is a monologue that has been written and rewritten with each presentation over the last 8 years, and which I will read aloud any time it is welcomed. It tells the fictitious story of an Antillean Military Force of 3.5 million recruits that attacks Manhattan, tomorrow morning at 0400 hours. It explains in painstaking detail its plans and strategies, pretending as if in fact the Caribbean had the same overwhelming military strike power as the north american military forces. Evey few paragraphs I emphatically state: “Just remember, this is theater”. This performance has many different intentions, anything from underlying the irony of the oppressed becoming the oppressor, to the idea that we could dream of being an independent, self-respecting republic, like most countries. I have had reactions from grown persons cry intensely on my shoulder afterwards, to others flat out cancel me out. I have come to understand with time that I am a very polarizing type of artist and have had to make peace with that.

NDEREO: Can you update me as to what is happening in Puerto Rico now? My image of the island is outdated. I hear about organic gardens, community associations, new economies, and more.

QRT: This is such a vast question that I would love to answer in detail, but alas, I will pick one subject. “Las playas son del pueblo.” The beaches belong to the people. As corruption has become visible in every aspect of social life on the Island, the arbitrary closing and sectioning of the public land has become our collective ideological battleground. It used to be the University of Puerto Rico; we had a glorious memento during the Summer of 2019 have impeached our corrupt governor; but now, we are fighting for a symbolic identitarian piece of land. The beach defines islander life, the idea of freedom, nature as god and now, a very concrete fight against the “cartels” that exist in our government: with the expediting of illegal construction permits; the impoverishment of local, real estate owners to then have banks foreclose and sell on the cheap to external capital and greedy developers; and a new law that invited billionaires to come and buy everything up and pay cero property taxes to us. It is insult over injury, times 525 years of systematic oppression.

NDEREO: There is such a gap between those who left and those who stayed. I remember how Puerto Ricans who left the island were looked down by those who stayed at home. The same happens with Dominicans. Dominican Yorks are still seen as lesser, lower culture, not refined enough, as something to be dealt with from a distance…and we keep our portion of the Island going with perhaps the biggest amount of money the nation receives. We send that money from New York and Europe, and that keeps the economy in Dominican Republic afloat. Is anything changing as to how Nuyoricans and New-York Ricans are seen and treated in the Island.

QRT: I wonder how many parallels DR and PR have in common, supporting the islands financially is certainly one of them. Nevertheless I do believe that humans have intrinsically a full gamut of emotions that range vastly from supportive to resentful and back. Each place of site comes with its own complexities. Having lived over a decade of my youth in north america, I feel I could attest to this gamut. One must not forget that each experience is real for whom is living it, and that, as they say, the grass is always greener. When abroad, we miss our roots, feel some sort of guilt and longing (some of what provides for excellent art making), when we consider who left, we see the better quality of life (employment, infrastructure, access to education, etc.) I cannot explain how everchanging these feelings are while we contemplate life’s uncertainties. I will say that it is never simple and that I feel we should continue to turn these conversations into the written word and ponder upon them. As long as economic systems oppress people, we will be divided and fight for crumbs under the table.

NDEREO: How would you say can we start breaking away with colonial and imperial modes of being that prevent us from connecting through the Caribbean? Dominicans are seen as lesser in Puerto Rico, although our economy is outpacing that of Puerto Rico and propelling the Island to become the most important center of commerce and tourism in the entire Caribbean region. Dominicans treat Haitians as lesser, generally speaking. Then there is the English and French speaking Caribbean, eons away from the Cuban, Dominican, Haitian, and Puerto Rican realities. How do we start to connect? Can creativity serve as a link?

QRT: Honestly, I believe that as long as political, military and economic oppression is the system we exist in, it is unrealistic to expect any other behavior from its inhabitants. We do resist, communicate and make a constant effort of allowing self perspective to inform our decisions, but it is not a simple task as we are in it. The prejudice towards Dominicans is shameful and I personally apologize for this. It is being phased out as long as political correctness and social equality continues to be a top humanistic priority. DR outpaced us many decades ago, this is true. Some Dominicans do have a prejudice towards Haitians and this should be re-examined. Regarding the idea of connectivity, I again say, in the beginning there is language. Being pluri-lingual is an enormous disadvantage. As poetic as it could be in other ways, being able to communicate is fundamental. I guess English is an internationally chosen language, so there is a starting point. Then there are non verbal languages, such as visual art, dance and music. Meetings for creatives such as biennials and such are of important relevance, but they do not constitute active economic, political or military agents for change. As creatives, we do our part to maintain a historic discourse present and alive, but we need less poetry and more economic shifting. Our political status will change once we stop being north america’s client and become a vendor to them.

NDEREO: I know this conversation has extended itself. So much to unravel with you. How is it to be a single father raising a daughter and co-creating with the universe? What are your challenges and blessings in this regard?

QRT: It is my pleasure to be considered, especially during these times. I feel blessed to be a single father raising a daughter. Having shared custody allows for me to have half of the year to invest in my art production in a concentrated and meaningful way. Then I come back to “real life” and allow myself to ponder on questions and actions such as: Am I raising a person that will reflect values of change and social progress? Am I being a good role model for her, allowing for conditions of a healthy self-esteem and self-realization? Either way, I do my best. I make mistakes and start again. I have a wanderlust for life. I am grateful for this.

NDEREO: I thank you again and my blessings to Puerto Rico and its peoples. You have been here for me. May the Island be safe and protected.

QRT: I am grateful for you, Nicolás. Abrazos siempre.

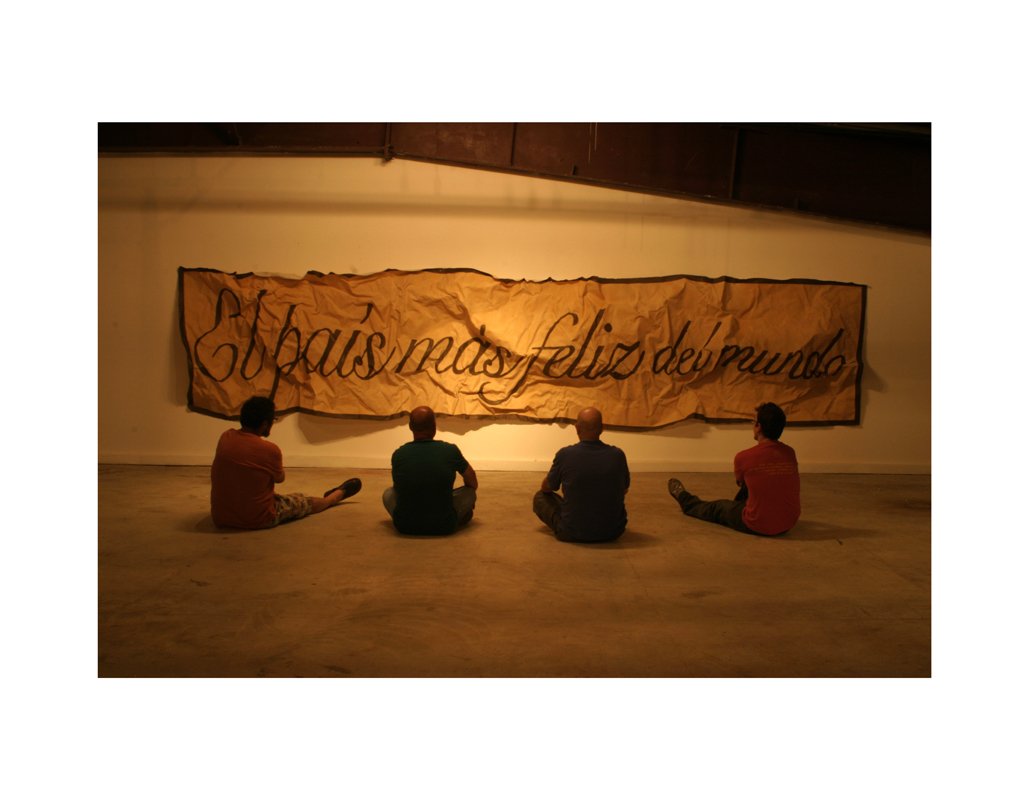

All images above courtesy of Quintín Rivera Toro

Quintin Rivera Toro / links to work and publications: Website / Instagram

Quintín Rivera Toro is a conceptual artist born in Caguas, Puerto Rico in 1978. He holds a B.F.A. in Sculpture from Hunter College, New York (2001); B.A. in Communications and Film Studies, from the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras (2007); and an M.F.A. in Sculpture from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island (2013). He has a Ph.D. in Art Production and Investigation with the Universitat Politécnica de Valéncia in Spain (2019). He has been awarded the German DAAD travel grant; A full fellowship for the Vermont Studio Center, in Johnson, Vermont; A studies grant from the National Academy of Design in New York City; He has been an artist in residence at the Ox Bow School of Art, S.A.I.C., in Saugatuck, Michigan; An intern at the Chinati Museum in Marfa, Texas; He was awarded an Achievement Scholarship from the Transart Institute in Berlin, Germany; An Individual Artist Grant as well as a New Genres Fellowship from the Rhode Island State Council for the Arts. From 2017-2019 he has was selected as the artist in residence at the Universidad Ana G. Méndez, in Gurabo, Puerto Rico. He was awarded the Puerto Rico Fellowship for the MASS MoCA studio program. Recently, the Bassat Collection Museum in Barcelona, Spain acquired his art work; and the Virginia Center for Creative Arts has awarded him a full fellowship for an upcoming residency.