Jenny Hawkinson

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Morel: Jenny, we met for the first time in person at Leslie Lohman Museum of Art, when I hosted a workshop and walkthrough for Transart Institute for Creative Research, during the run of INDECENCIA, the exhibition that I curated. Later on, we worked through Transart as you were developing your thesis and project for the MFA that you were pursuing at this organization. It was inspiring for me to see your commitment to Feedback Loop as this developed over the six months we communicated and met virtually. Can you describe this action so that we set the platform to further discuss this here?

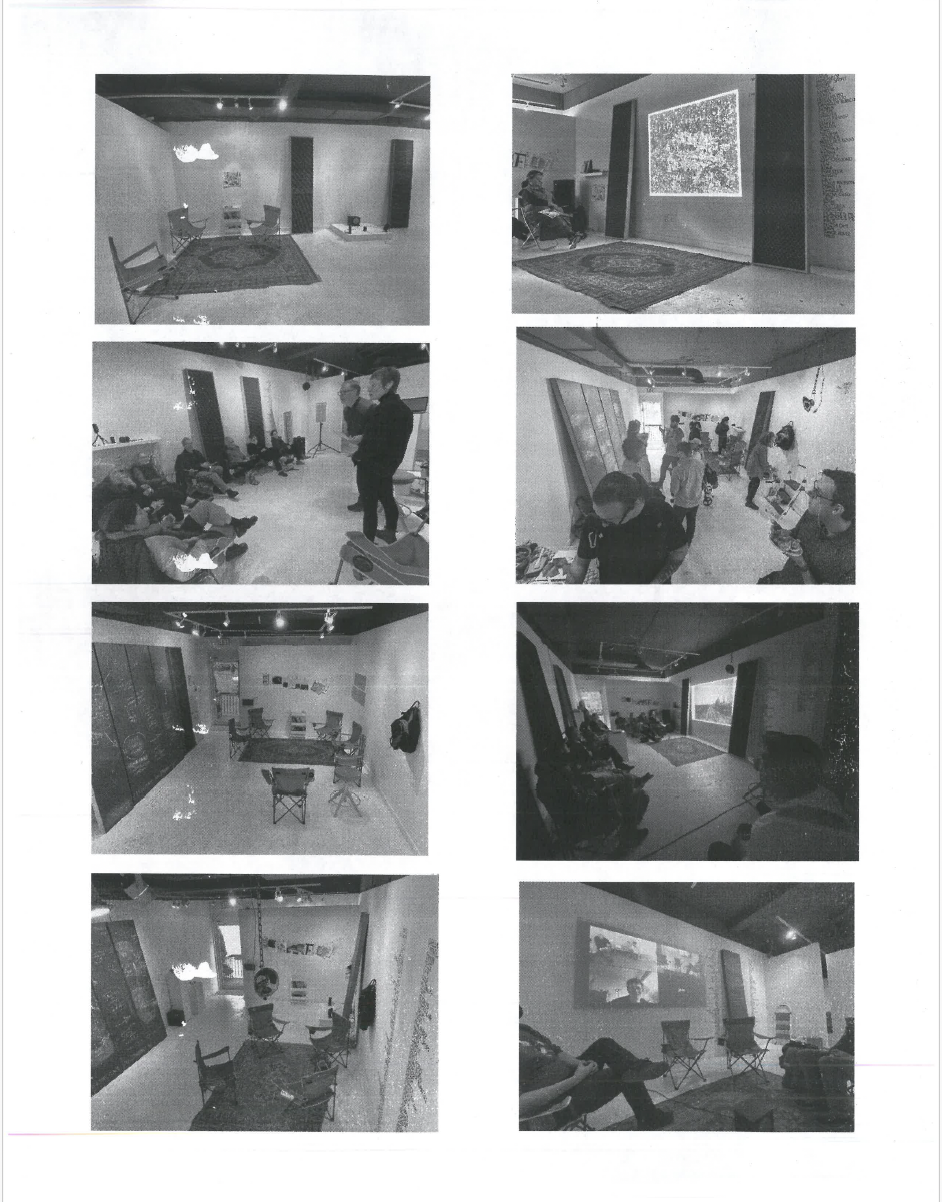

Jenny Hawkinson: Thanks, Nicolás. I remember that our first meeting was an online intensive with Transart Institute. You invited us into a somatic exercise exploring different rooms in our homes as a way of inhabiting our practices. I was inspired to weave my interest in conflict engagement studies into my practice through my other advisor, Dorit Cypis, who is a contemporary artist and professional mediator. Sound art became the primary medium when I discovered that analogue feedback, mediation and community organizing all require proximity for anything generative to happen. The feedback loop became a conceptual framework for the residency and took place at Bothkinds Project Space in Vancouver. The gallery was transformed into a provisional gathering hub to accommodate lectures, artist talks, performances, rehearsals, film screenings, potlucks, a reading room, an open studio and a community drop-in centre. Feedback Loop was a d.i.y. community-engaged residency that sought to engage the public in collective listening and sounding practices in an effort to build resilient intersectional communities.

NDEREOM: As you mention, with Feedback Loop you issued a call to communities and people passing by the gallery to join you in a series of simple, yet carefully organized events. Can you give a couple of examples of what took place there? Can you talk as well as to how the perception of what an art gallery might be shifted depending on who attended the events and what they were seeking to find or willing to gift to you and to the space?

JH: After six months of mostly solo research I began communicating with artists, curators, musicians and community organizers to gauge their interest in the project, specifically around challenging the public perception of an art gallery as an exclusive space. In the first week of opening I hosted a meal for these early collaborators. At the meal I was encouraged to share my feedback loop origin story. It happened while I was recording my dad’s voice posthumously on the answering machine. I accidentally initiated a series of screeches and drones with my recorder. The feedback harmonized with his words: Hello, this is Paul…

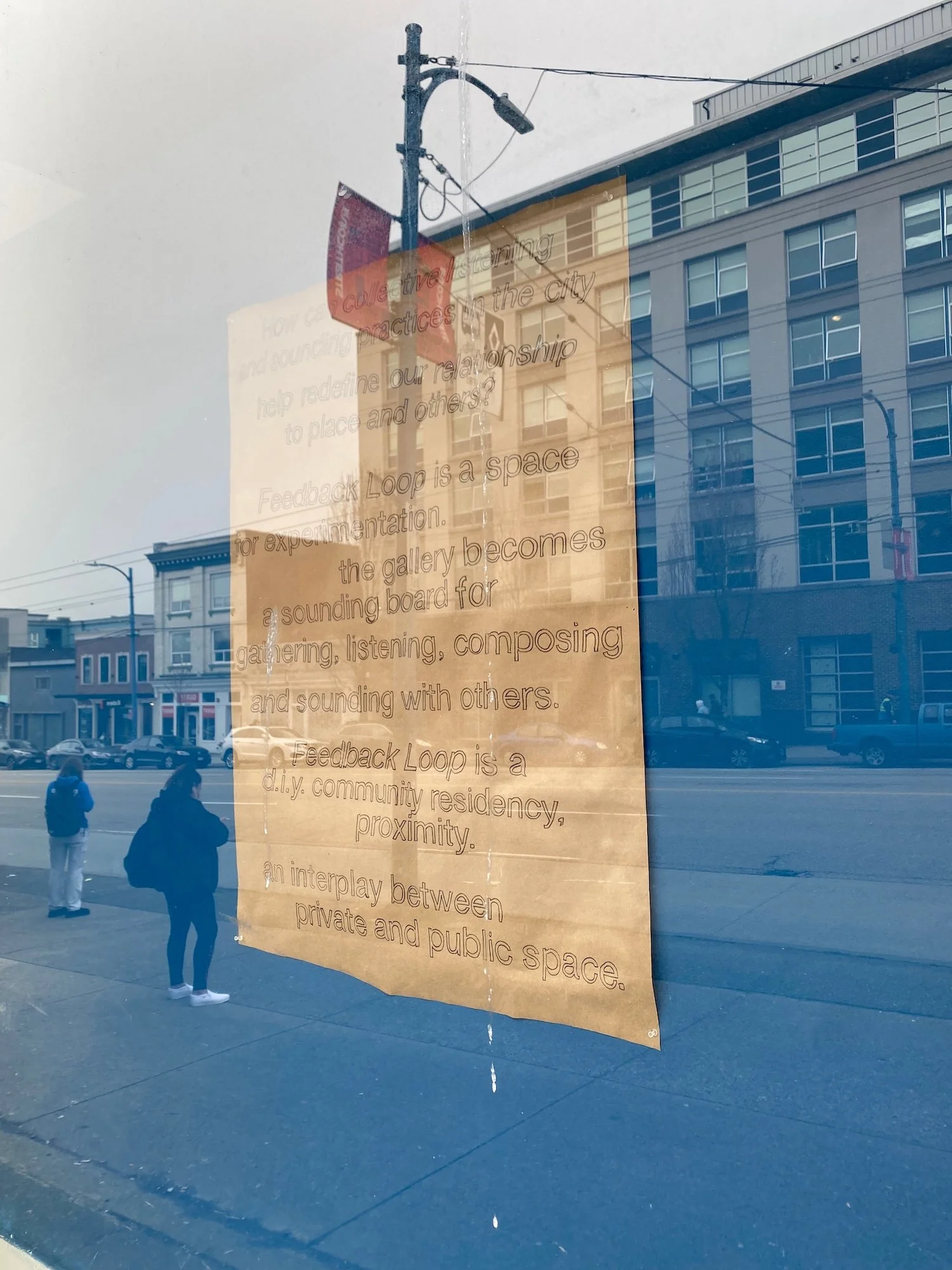

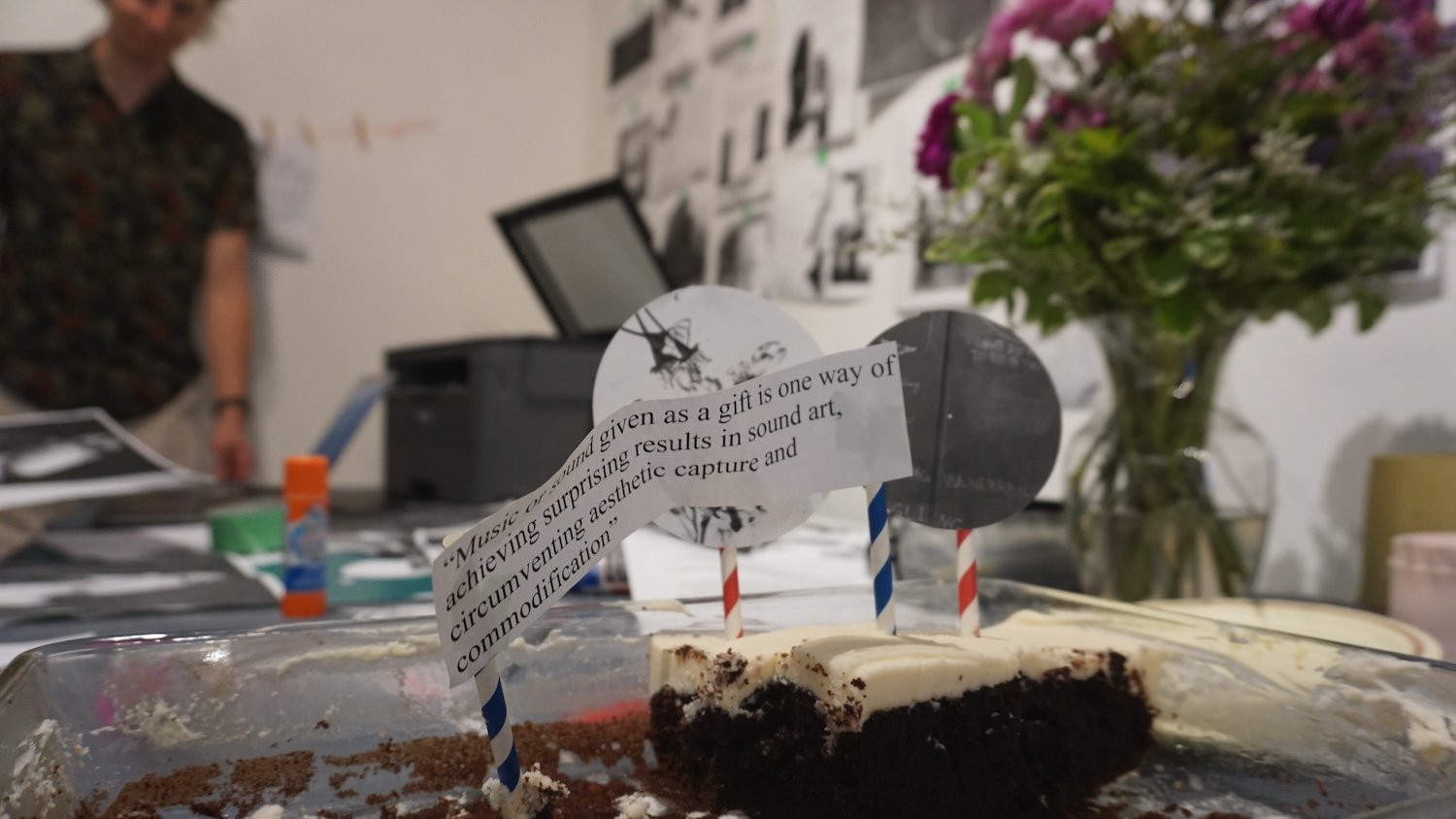

This tender story gave us permission to connect on a deeper level. There would be many meals to follow where we listened to each other and spent non-productive time together. It also set the precedence for participation by sharing food, stories and poems and created an “in” for people who didn’t consider themselves artists but wanted to be involved. The aesthetics of the residency were punky and provisional. In lieu of placing an artwork in the gallery window I wrote a manifesto. It was essentially an invitation to come and play: Feedback Loop is a space of experimentation. The gallery becomes a sounding board for gathering, listening, composing and sounding with others. The window was updated weekly with the schedule, which worked surprisingly well for bringing people in. I built five large acoustic panels that could be rearranged to accommodate the events. They also doubled as chalkboards and provided a focal point for the ideas behind why we gathered. The sentence written near the bottom of the chalkboard by many hands underlines the ethos of our collective practice: This studio is a safe place for struggling and vulnerability.

Together we built a listening library which consisted of a hand drum, a battery operated crow caller, a CD of Pavarotti’s Greatest Hits and a vintage answering machine an Irish bodran beater and other odds and ends. On occasion songs were gifted to the space. Deborah Charlie, an Indigenous choreographer and song writer, offered a blessing song. Another visitor asked me to record him singing in Tamil, his mother tongue. Another guest gifted us with a water song from her territory. The programming was community-initiated. We hosted a lecture on the Mathematics of Feedback Loops by Sandy Rutherford, the director of the Complex Systems Modelling Group at Simon Fraser University. Cathy Busby conceptualized and facilitated the call and response procession, Parking where we traversed the entire length of Cordova Street from east to west. She called out the names of each parked car in a sing-song voice and we mimicked her. Wade Comer hosted a listening party with cassette tape loops he made in the early 1990s. James Witwicki led a soundwalk through the Strathcona neighborhood; inviting participants to listen intentionally beneath cherry blossom trees. This is a small selection of the events we hosted.

NDEREOM: How long was Feedback Loop active? I recall my suggestion to find a place that would allow you to keep the events going for a whole year, at least. Time is of so much importance to this kind of creative endeavours and I understand that the real estate situation in Vancouver is fierce. With this said, I am wondering as to who attended the different gatherings and if you were able to cogenerate an ecology that made room for participants beyond the conspicuous art audiences who dress in black and go to openings.

JH: It was originally planned for five weeks but was extended by two months. That felt significant, time is precious in the Downtown Eastside. Deborah Charlie, who used the gallery for rehearsal space, sadly passed away last summer. Deborah took care of me when I got a concussion the day before the opening. She convinced me to sit down and rest while others prepped for the event. Kinship and deep listening took on a sense of urgency in a place where life feels more fragile. Feedback Loop challenged the scarcity mentality of Vancouver by leaning into an alternative gift economy. The care that was cultivated from so many people fuelled my belief that generosity begets generosity. It defied easy descriptions. For some Feedback Loop became a drop-in centre for food and camaraderie. For others it was an open studio for creative work and collaboration, and still others a space that provided interesting events to attend in the evening. Those groups often overlapped.

NDEREOM: I am very sorry to hear about the death of Deborah Charlie, who acted as an angel on your path. I am into your aesthetics, which are pretty much homemade and DIY. I have had enough of glitter and shiny stuff in the Art Industry, as well as objects made for collectors to hang behind their sofas. What did Feedback Loop generate, organically, in terms of evidence?

JH: Thank you! I love art that is ephemeral and community-engaged. Early on I shifted from making art for the gallery to creating work for the streets. This aesthetic and sense of social responsibility carries my practice today. The residency was like a zine in the way that it accumulated people, photocopied materials, sound bytes, recordings and objects that all make up the bigger story. There was other ephemera as well; local filmmaker and analogue sound enthusiast Ryder White set up contact microphones on poles outside the gallery. The sounds were transmitted through a rotary phone and a stereo speaker hanging from the gallery ceiling. Cathy continued Parking by hand-printing every vehicle name we sounded during the procession into a series of columns on the gallery walls. The remnants of Reza Eném’s Ada Acara Pengantin performance were also on display; an assortment of random objects that people gave as “wedding gifts” for the faux Indonesian roadside wedding. To get even more ethereal, Feedback Loop also exists as traces of memories for those who witnessed and participated.

NDEREOM: When I think about Vancouver, Gabor Maté comes to my mind. He is the addiction expert who has worked so closely with individuals and communities in your city. Are you familiar with Maté? What is the Vancouver that you were dealing with at the moment of shaping or co-shaping Feedback Loop? Who did it involved, and who was helping and supporting you? Were there any layers of the city that the process of generating Feedback Loop helped you see for the first time, or perhaps corroborate?

JH: I read his book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts when I first moved to Vancouver. At the time I was working in a drop-in centre and meeting individuals who lived the very scenarios he wrote about. It’s a small community; I’m sure we know the same people. It seems that since then, the opioid crisis has eclipsed all other issues. This neighborhood is swimming in unresolved grief. To add to that, the housing market is rough. If gentrification was about bringing together social demographics towards a mutually hospitable neighborhood then we would be in a great place. The ratio of market rate to subsidized housing in the Downtown Eastside isn’t enough to keep up with the extreme need. New development increases rents for storefronts which create financial challenges for the non-profits and arts spaces that have been here for years. Lack of resources feeds into a spirit of competition rather than collaboration among organizations working for similar causes. That’s not to say that there are some incredible community groups down here, but overall this is the context that inspired me to create a research project about sounding the city and to facilitate a d.i.y. community residency that focused on generosity and connection with ‘the other’ through listening. Indeed the community rallied! Choreographers Lance Lim and Deborah Charlie activated Feedback Loop with playful, intentional and spiritual movement; sowing into the general atmosphere of curiosity and creation that defined the residency, as well as identifying the importance of access for such spaces. Reza Enèm participated as a guest artist to introduce the sounds of his city to the sounds of our city in the spirit of nongkrong; an Indonesian concept of “non productive time” spent with others. A local artist collective led an improvisational drone session in the gallery on what we later found out was World Drone Day. Our sounds effortlessly fused with the soundscape from the street. We hosted a screening of short video works about sounding the city from a handful of local artists. My role as an outreach worker meant that sometimes the gallery felt like a drop-in centre. People I know from the street would drop by frequently once they realized I was “in residence.” Through Feedback Loop we touched on various experiences of sound and the connection to class and environment. The project unfolded like a decentralized orchestra.

NDEREOM: You had some kind of a wake for the closing of Feedback Loop. What were you and those who attended mourning? What would you say continues to be and exist of Feedback Loop, past its presentation, in the gallery, the city, and the communities who co-created it?

JH: The Wake invited people to reflect on the collective experience and imagine what it could become. We mourned the closure of another space in the neighborhood for connection, creativity and participation. People have been collaborating on a smaller scale by sharing ideas and supporting each other. Recently a video artwork that James Witwicki and I produced during the residency called Homeless Sound Poem was screened at the FLUXUS Experimental Film Festival in Ontario. Cathy documented the procession and is developing her piece into a madrigal-like choral work that will be performed at St. James Church on Cordova Street where we mustered for Parking. I also hope that by adding to the lexicon of community-engaged artworks and communal sound studies in Vancouver, Feedback Loop is a work that other artists can build on. Feedback Loop personally solidified the value of working with others and left me wanting more. I will continue to explore the interface of the studio and the streets within my practice.

NDEREOM: I would like to move to Floathouse. This action is a moving piece of poetry and I know so little about it. I enjoy your use of materials; discarded stuff that you repurpose to set free on the waters surrounding Vancouver. Tell me about it.

JH: I made Floathouse in 2016 during a residency on Vancouver Island. Alert Bay takes a day to travel from Vancouver, yet there are close times to my neighborhood within the indigenous communities. I constructed a miniature houseboat with found materials and built a narrative around the house floating from Northern Vancouver Island to Coal Harbour in Vancouver. I was thinking of home, and what it means to relocate from a small town to the city. It’s loosely autobiographical. The artwork speaks to the complexity of familial ties and the disorientation that comes with this migration. The coastlines of B.C. are widely beautiful but also hold a dark history of colonial violence, potlatch bans and residential schools. In the church on the reserve they sing about the “children of East Hastings,” family members who have been lost to the streets because of generational trauma. The through line between this piece and my recent work is a rootedness in the community and a desire to make work that people can emotionally connect with.

NDEREOM: Colonial trauma is so embedded in this whole hemisphere. You visited me in the South Bronx, where we walked along the Bronx River and ate coconut dessert that we got at a Dominican Bodega. You saw my place and you can attest to my love for everyday objects. With a few exceptions, I am not so much into Art objects, or things artificially fabricated to be traded. I like old photographs from people and families and events. I am surrounded at home by Catholic icons and by memories from hospital visits, and signs and items from stores long-gone, among others. I would like to know about the action where you deal with souvenirs left to you by your grandmother.

JH: The Sands was part of my broader research of homeland, contested territories and displacement. I’m fascinated by what people choose to keep and how these objects hold space emotionally. My Great Grandmother was an avid traveler and collector of souvenirs. She had a basket with rocks and containers filled with sand and water from pilgrimages to Israel/Palestine. When she passed away I inherited her collection. One day I wondered, what if I brought the sands back? I wanted to follow my Great Grandmother's footsteps and also explore the geopolitical ramifications of “return” in that place. I’m neither Jewish nor Palestinian and my primary connection to the land was through my faith and her collection. I tried to prepare myself but no amount of reading could prime me for what I witnessed in the West Bank. Bethlehem was home-base for a month and I got to know several artists and wood carvers. I learned how to make an olive wood figurine with some carvers near Manger Square for a couple weeks. The repatriation of the souvenirs took me to Hebron, Masada, Ramallah, Nablus, the Galilee and East Jerusalem.

NDEREOM: Talking about travels, you are involved in a residency in Washington State focused on water. What do you have in mind for this, socially? I am asking because of the ways you think when bringing people together, and because of your interest in debates, conversations, mediation and the like.

JH: Convening Bodies was co-founded by Paige King and myself and shares a lineage with Feedback Loop in its relational focus and accessible ways to participate. It came about from several conversations between us after grad school. Our practices intersect at points of conviviality, kinship, and a multilayered interest in the ocean. The Convening Bodies Residency brings together artists and practitioners from across disciplines and continents to convene near bodies of water. It encourages engagement with how we relate to bodies of water, marine environments, the Ocean at large and one another. In September we gathered between two coastal regions in Washington State where Paige and I have familial connections. During the residency we explored how situated studies and different perspectives and understandings inform an ecology of care within a creative practice. We went with the low residency model as an extension of that care because borders prevented at least half of the residents from participating in person. Daily video calls created a rhythm for practice sharing across distance and and online platform was the “studio space” for our research to be gathered and collectively digested. It worked quite well, conceptually. Land separates water and yet all water is connected. In November we shared our works in process from the residency as an exhibition within a wider research project called Near Dwellers as Indwellers; a show that explored multi-species encounters within urban environments. It was exciting to see the work from Convening Bodies in the same room.

NDEREOM: I would have loved to join you and my river was full when this happened. It sounds like the residency went great. Thank you, Jenny, being in conversation with me. Is there anything that you would like to ask me?

JH: Thank you for inviting me into this space! I am curious what projects you’ve done in the past that stand out to you as pivotal moments that have shaped your artistic practice? What are the through lines of your work when you take a step back and look at the bigger picture?

NDEREOM: One experience that shifted so much for me was Pleased to Meet You. For this, I relocated from my home in the South Bronx to Calaf, a town an hour or so from Barcelona, with the intention of meeting its inhabitants. INDENSITAT was the organization that hosted me there in 2007. I could write extensively about this, but there is a publication documenting my sojourn in Calaf, which I am sharing HERE. Prior to this, I have worked with communities and groups, yet never with a whole city. Pleased to Meet You made me reconsider a great deal of what I did before and what I continue to do today as a creative. I returned to Calaf this past summer and gathered with a group of my neighbors there. I was able to do this thanks to Plataforma Vértices, Anna Recasens, Thelma García, Laia Solé, Nuria Corominas, and Luke Dixon, among others who made my return possible.

As for looking back, I see myself as taking such risks with the work I do that I often say to myself how, “I would not that again,” meaning engaging in the same action or experience twice. For me, art is about self- and communal transformation. Forget all of the trappings, including trendy galleries and-up-and coming curators, and it is indeed a spiritual experience of the most profound kind. Having a piece of coca in a Catalonian town or city with neighbors you love; that is art to me.

All images courtesy of Jenny Hawkinson

Jenny Hawkinson’s related links: Website / Instagram / Contact

About Jenny Hawkinson:

Jenny Hawkinson is an artist and researcher who focuses on place-based research through a methodology of gathering. She works in video, textiles, soundscape, sculpture, installation and public interventions. Her work poetically transforms gathered and found materials and often explores themes of contested territories, anti-monuments, border politics and psycho-geography. Her interests in borderlands came from years of ‘unlearning’ as an expatriate of the America. Over the years she’s held independent artist residencies in Belfast, Northern Ireland and Bethlehem, Palestine. Alongside her artistic research is a commitment to being socially-engaged and community-focused. Locally, she has collaborated with Illicit Projects, a guerrilla theatre troupe grown from the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. She has lead several community murals and facilitates intersectional community development with the arts.

In the Spring of 2024 Jenny formed and facilitated a d.i.y. sound based artist residency that was open to community members throughout her neighborhood, whether they were artists or not. In July 2022 she performed a collaborative sound intervention, Call & Response beneath the Burrard Street Bridge in Vancouver. In addition to several group shows throughout the Pacific Northwest, Hawkinson’s solo exhibitions include Beyond Barrier at the Fort Gallery in Fort Langley, BC (2019), Origin Stories at the Bleeding Heart Art Space in Edmonton, AB (2018) and Promised Land at the Yactac Gallery in Vancouver, BC (2017). In 2019 she was invited to the Czech Republic to speak about the intersections of art, faith and community development.

Hawkinson received a BA in Visual Arts from Trinity Western University and an MFA in Creative Research through Transart Institute (2024). She lives and works in Vancouver, BC on the unceded and traditional territories of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) and səl̓ílwətaʔɬ /Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations.