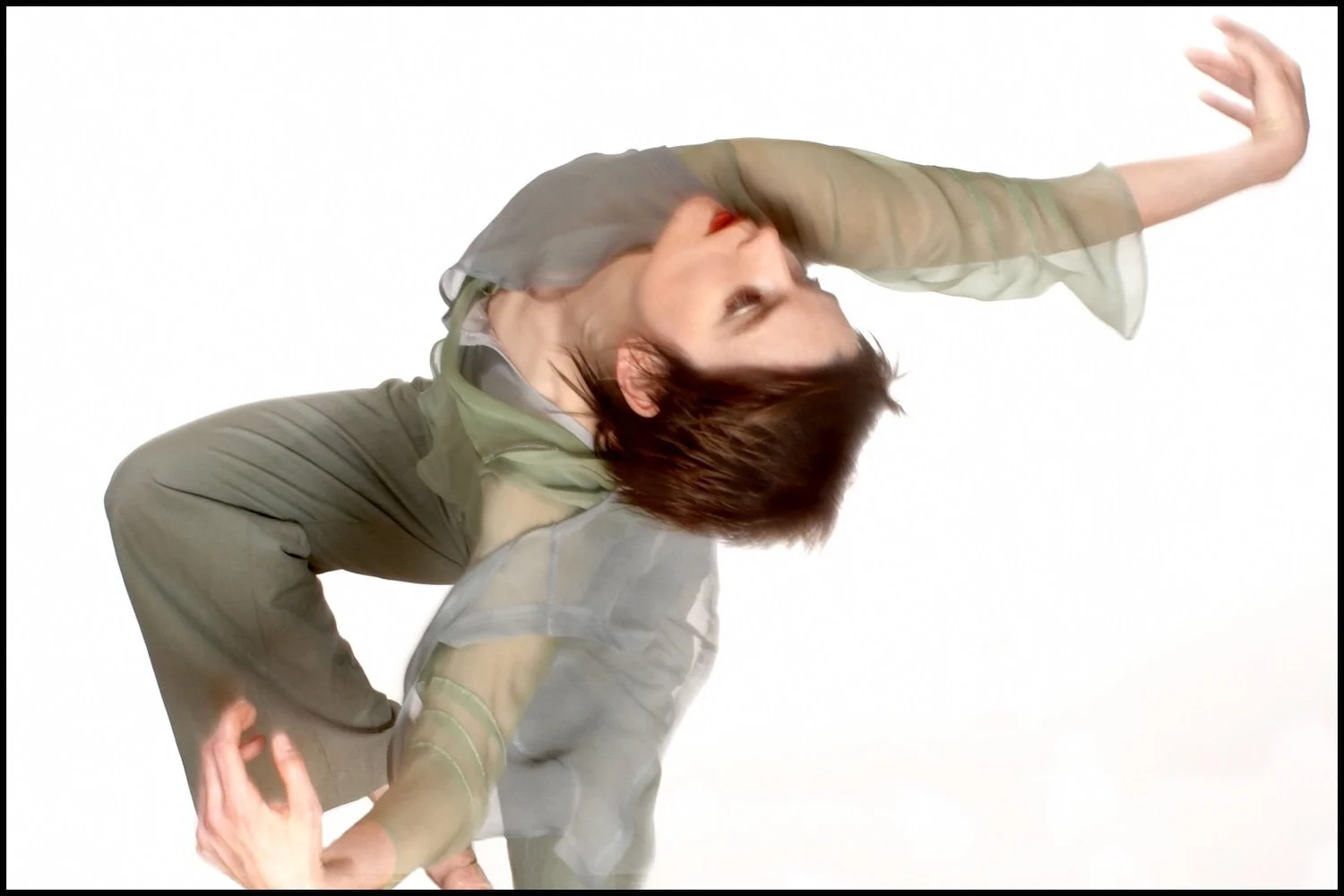

Heidi Strauss

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Morel: Heidi, we met at Transart Institute in New York. This is the program I have been connected to since 2009. I am happy that we crossed paths since dance and movement play a central role in what I do, creatively. What are you dancing or moving with at this moment?

Heidi Strauss: I’m happy our paths have intersected too Nicolás, and grateful for this conversation.

These days, I’m preoccupied with tenderness, and how space is held between people. I’ve been rethinking my interpretation of the performance container from a particular site or space, to the relational or to the space (and what is contained) between people. I’m interested in invisible and felt connection, the imprint/trace of human presence, and its impact.

I keep (re)learning to let the body lead, trusting its intelligence and giving greater space to natural, involuntary responses in the creation of movement. With the baggage of dance training, habits of designing movement can feel intuitive but are built on deeply embedded patterns—like most lived experience. So, to answer your initial question, I’ve been dancing and moving to listen —to where I am in the moment, who I’m with now, and how I’m with them.

NDEREOM: Who are those that you invite to dance/move with you, and how are the relationships with these collaborators built? In my case, I work with friends and people with whom I have affinities. My premise is that it is quite difficult, not to say impossible, for me to work with people I would not be interested in being friends with. This is not because of nepotism or because we have to agree to all, but because there has to be some kind of resonance for me to be able to collaborate with another person.

HS: I’m answering this question, as it happens, from a mini residency near Caledon, in the countryside about an hour from Toronto. I’m here with two people I met teaching in a theatre program at Humber College: Fides Krucker, and Alex Fallis. We co-directed an ensemble work there in 2010 called unfinished passage. And later Alex and I co-directed a contemporary opera that featured Fides Julie Sits Waiting written by a score by Louis DuFort. I can say those experiences fostered a long-term artistic relationship and friendship. We are here now in this residency collaborating with four other performer/creators who do voice training with Fides. We are from different generations and disciplines, trusting what we have to learn from each other, where we meet in the middle, how we share practice. We’re researching human connection and the question of bonds—how are they built? how do they exist? how are they maintained? what conditions are necessary for them to form?

As an emerging artist, I used to collaborate with my peers and could feel that our creative energy was wrapped up in our interpersonal relationships. The investment in working together toward a creation/performance felt exciting and powerful because it was shared. At this point, a lot of my peers have moved onto second careers. In the choreographic work I’m developing now, the dancers all belong to a different generation than I do. That generational difference is always present. I need to work differently to meet them in a process, to understand their language, influences, ways of thinking, boundaries. Some of these differences used to be understood. Now I am conscious of them (most of the time) and try my best to work against the hierarchy that age and experience can create in a room, and to understand who I am in a particular configuration of people. I actively try not to play or ‘perform’ any role, but to continue to be my searching, listening self. This is how I keep learning.

I think any collaboration involves deep curiosity and trust in the people you are with. This feels clearer and easier when there is a shorthand. I work with my partner Jeremy Mimnagh on many projects. He creates the sound worlds, sometimes does projection design, photographs and archives creation and performance. He digests what is happening differently than I do; he sometimes completes, sometimes counters, and always deepens the questions work asks. I am lucky for that. It reminds me how vital it is to find the right forms of communication, specific to individual collaborators. In dance-making some of that communication is non-verbal—a felt-sense, an intuiting. When considering dancers for a project, this is always one of the harder-to-define criteria. How do you know, until you know?

NDEREOM: In your research you focus a great deal on audiences. Linda Mary Montano has written about audiences in regard to performance art and art in everyday life. I have applied most of Linda’s thinking to my own work and I have come to the conclusion that, as I move further and further into life with what I do creatively, my audiences have vanished. We are all in the action or inaction together. How has this been for you?

HS: I like your phrase ‘we are all in action or inaction together’ for what it registers about the larger forces of collective knowing and understanding. I believe experiencing art is a necessity for different people at different stages of their lives, a method to make sense of what feels complex, experience other perspectives, participate in something that stimulates the mind or imagination. Being an audience member often asks that you give over to the experience ahead of you. I don’t think of this as a loss of control, but as trust—trust that you will be guided through an experience that is meant to be an offering. However, the culture of engagement is changing, and the pace and expense of life are driving people in other directions now.

I keep telling my teenage son (and myself) that a day will come when the power goes out, when everything we are accustomed to in the realm of technology and electronics will literally be unplugged, when all we will have will be our bodies and minds and how we interact with others and the natural world. Stripped back in this way, I imagine there would be a different form of attention-giving. There would have to be. But for now, we are conditioned by bite/byte size forms of engagement. These many demands on attention make durationally longer or deeper propositions challenging. Sustained commitment is a lot to ask for, but it doesn’t mean we stop asking.

NDEREOM: The body is certainly not obsolete and it will come in handy as the world collapses further and demands from us face-to-face encounters, rather than mediated ones. This encounters, in my opinion, will entail honest conversations with Earth, family of any kind, energies, spirits, and non-human creatures. The screen has become an excuse, a filter, a boundary, and a border. Many have lost the ability to pick up a phone and call another person. It is now consider impolite not to text before calling. I find this preposterous. If the person can’t take a call, they just do not need answer.

The body is a central element in your work. There is so much conversation about embodiment now. It is as if we are collectively rediscovering the body. I am wondering if you can speak as to what this may point to? Is what we might have lost bodily speaking recoverable or does it entail new engagements with hands and hips and our cellular universes?

HS: To be honest, I am not sure what the term embodiment means now. I agree it is overused, especially in academia. This might be one of the moments when language fails, or a fixation with pinning an idea on a word wins. I feel the word itself is often used performatively, and it’s important to keep in our consciousness the reminder that bodily intelligence is always present, mysterious, and then also deeply intertwined with complex aspects of our personal selves. But I am not sure we have lost anything bodily speaking, except the capacity to choose time to be with, and be curious about, our bodies. With the provocation of choosing to use that time differently, comes the possibility of recovery.

NDEREOM: Great point about embodiment. I feel the same way about self-care. There is a proliferation of language around it, yet the ability to engage with discomfort seems to be quite low. But, do tell me about any relationships that you may have found or intuited between movement and stillness? Are they opposites or part of a continuum?

HS: As a teacher in improvisational settings in a western-based form, I observe how movement is usually chosen over stillness. Feeling active—‘in the action’—brings a satisfaction that comes with expending effort. My mom, into her last days, regularly said: I need to move. Moving makes us feel life is moving with and through us.

But in stillness there is also movement.

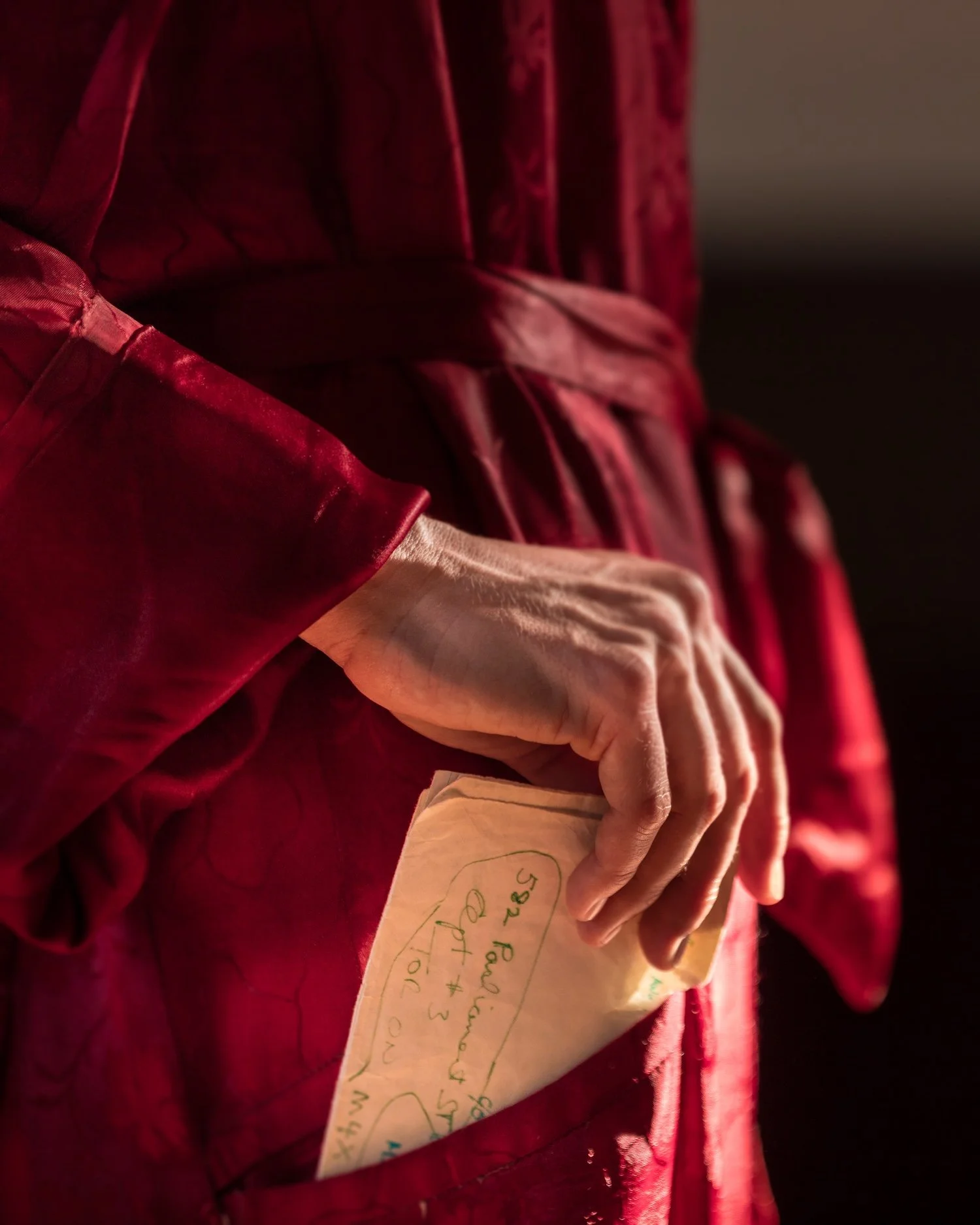

In the late 1990s, I performed a solo by the late Murray Darroch called Grey Lipstick. I had just graduated. Murray was a choreographer, the school’s General Manager, and my ballroom dancing partner. His partner had recently passed away amid the AIDS crisis. In this solo I slowly remove and unfold letters from my pockets that sail to the ground, unroll colourful men’s silk ties that fall through my fingers, and let 4 silk dressing gowns slowly slip off my body as I imperceptibly walk slowly forward on a long diagonal—always looking ahead, never changing the pace of the movement. Set to Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, I leave a trail of shimmering colour and memories behind me. The solo was very much about giving in to a slow continuum. Not long after performing this, I was introduced to Butoh and learned how to work with different densities in the body. This was a huge lesson for me because until then my understanding of the body in motion had revolved almost exclusively around a western approach to movement. When I performed Grey Lipstick that first time, I will never forget hearing someone in the audience ask: when is she going to start dancing?

NDEREOM: “when is she going to start dancing?” That is hilarious. I have been dancing since I was in my mother’s womb. I guess, many of us have done the same as we developed in the dark. Later on in my life, my family taught me Merengue steps. I do have to say that my mother is not really a dancer by Dominican standards, but she dances some. All in all, this happened in a context where dance is medicine and Spirit. Is there anything that you might want to say in terms of dance as healer or dance as medicine?

HS: I feel like my life path in dance has helped me understand physical behaviours and given me a felt/empathetic understanding of the situation of others, but that is not really your question. Yesterday was the hottest summer day we’ve had so far this year, and I was in a group conversation around a piano in the forest with 7 other women. We were asked where our garden/refuge was. Responses were mostly about being in nature, floating in water, being held within a canopy trees, caught in shafts of sunlight. For me it was anywhere—anywhere I could dance by myself— the garden space inside. I do think of dance as healer, I think that is why I am still doing it. I think the body does miraculous things and can harness individual and collective energy in indescribable ways, and beyond definitions of embodiment. I don’t come from a culture that uses dance to gather—to celebrate or mourn. I wish I did. For me dancing is my place to celebrate and mourn, and to understand what I can’t name.

NDEREOM: I envision all us, all over the globe, partaking of collective dances and choreographies to shake the trauma of the recent pandemic off, which to me is still here and happening at an emotional level. If you were invited to give these post-pandemic dances a shape, how would they look? Would you be willing to put into motion, some day in the future, one of these choreographies with The Salon at an open space in the South Bronx?

HS: I would put into a motion a slow procession of bodies moving through public space, bodies moving with sustained attention, force, and collectivity. Periodically one or two people from the rear of the group would move through the bodies in real time, to take a place at the front. In this cycle, everyone would experience leading and listening to make a powerfully gentle statement about the importance of sharing space in our time here. Of course, to do something like this somewhere that is not my home, or familiar to me, I would want to work closely with you, or someone who intimately understands the South Bronx and its people. It would be an honour to do something like this. And I’d hope there’d be a bit of a dance party at the end, too.

NDEREOM: Let’s. Can you suggest some movements to help me/us be with deep sadness?

HS: Hmm. To move with deep sadness but to feel more of my/your possibility: a simple act of opening into the world by stretching different aspects of the surface of your body into the space around you—as if moving into a welcomed touch. Akin to the feeling of how the soft palette stretches when yawning, translate this yawning to the outer surface of the body, to your cheek, or your belly, or your middle back. In this way, one part of your body searches for how far it can go/feel, and the rest of your body involuntarily compensates to counterbalance you; a reminder of the natural give and take we are capable of, and the capacity for resilience we carry.

NDEREOM: Can you suggest some movements to help me/us mend all of my/our broken parts with great love and compassion?

HS: Backwards walking. A contemplative practice that opens layers of perspectives, plays with sensory attention in the body, three dimensionality, and trusting the unknown. (I know you have done a practice like this with your work—The Sounds of Slowness, I think it is called?) I have been engaged in a practice of backwards walking with Marie-France Forcier, and He Jin Jang over the last three years. We met at Transart, and this practice connected aspects of our respective research. Here is a little documentary from our 2nd residency where we gave a workshop called Navigating Uncertain Terrain with Generosity.

NDEREOM: The piece you are refering to is For At’s Sake. For one of the 7 pilgrimages that I undertook, I walked backwards for two days from Lower Manhattan to The Bronx Museum. What compels you to move? Why dance?

Dance allows me to make sense of myself and the world, to be close with myself and others, to be in the moment. It teaches me about life and helps me process experiences. It can be joyful and exhilarating but demands practice and commitment if it becomes a tool to connect with others. It reminds me about process—that things take time. Sometimes it reminds me about why I am here.

NDEREOM: Why do you really dance? Why do you must absolutely dance? No More questions asked after this—for now.

HS: My mom was a devout Catholic. I grew up in a household and had an extended family with deep ties to Catholicism. I would sit beside my mom on Sunday mornings and wonder about patriarchy, and why people always had so much to apologize for. I stopped going to church when I left home to study at the School of Toronto Dance Theatre. I found in dancing the closet thing I understood to spirituality, and to a kind spirituality that somehow extended beyond the individual. I found space that was welcoming to expressive bodies and minds in their imperfection, and to different forms of togetherness. I found space populated mostly by women and queer folx and participated in daily practice that made me consider the connection between ephemerality and mortality - lessons in making each moment count.

NDEREON: I was not aware of your connections to Catholicism. That has been my case, and I continue to draw inspiration from its rituals. There is a pull to this I cannot forgo. Are you familiar with Peter Occhiogrosso’s Once a Catholic: Prominent Catholics and Ex-Catholics Discuss the Influence of the Church on Their Lives and Work. I thank you.

HS: Thank you, Nicolás.

All images courtesy of Heidi Strauss / All photos: Jeremy Mimnagh

Heidi Strauss’ related links: Website / Instagram / Facebook / Contact

About Heidi Strauss:

Dance artist Heidi Strauss has worked for companies and choreographers from across Canada, as well as within Europe and Asia. A multi-Dora Award winning choreographer and the Artistic Director of Toronto-based adelheid, Heidi has been a resident artist at The Duncan Centre (CZ), and in Toronto at the Factory Theatre, The Theatre Centre, Harbourfront Centre, and currently at The Citadel through their Creative Incubator program. Her installation work has recently been recognized by UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network. She has been commissioned by/choreographed for Toronto Dance Theatre, Mocean Dance, The Frankfurt Opera, The Canadian Opera Company, Volcano Theatre, the Stratford Festival, among others.

Through adelheid she initiates opportunities for other artists, recently including ‘re:research’ for emerging dance creators, ‘space’– a pop-up for creation and practice towards pandemic recovery, and ‘cohort’ for creators integrating smartphone technologies into their performance-making practice. Heidi is a KM Hunter Award recipient who continues to evolve her teaching practice relative to her creative explorations; she has given workshops across Canada and internationally.