A Pilgrimage to Linda Carmella Sibio / A Travelogue on the California High Desert

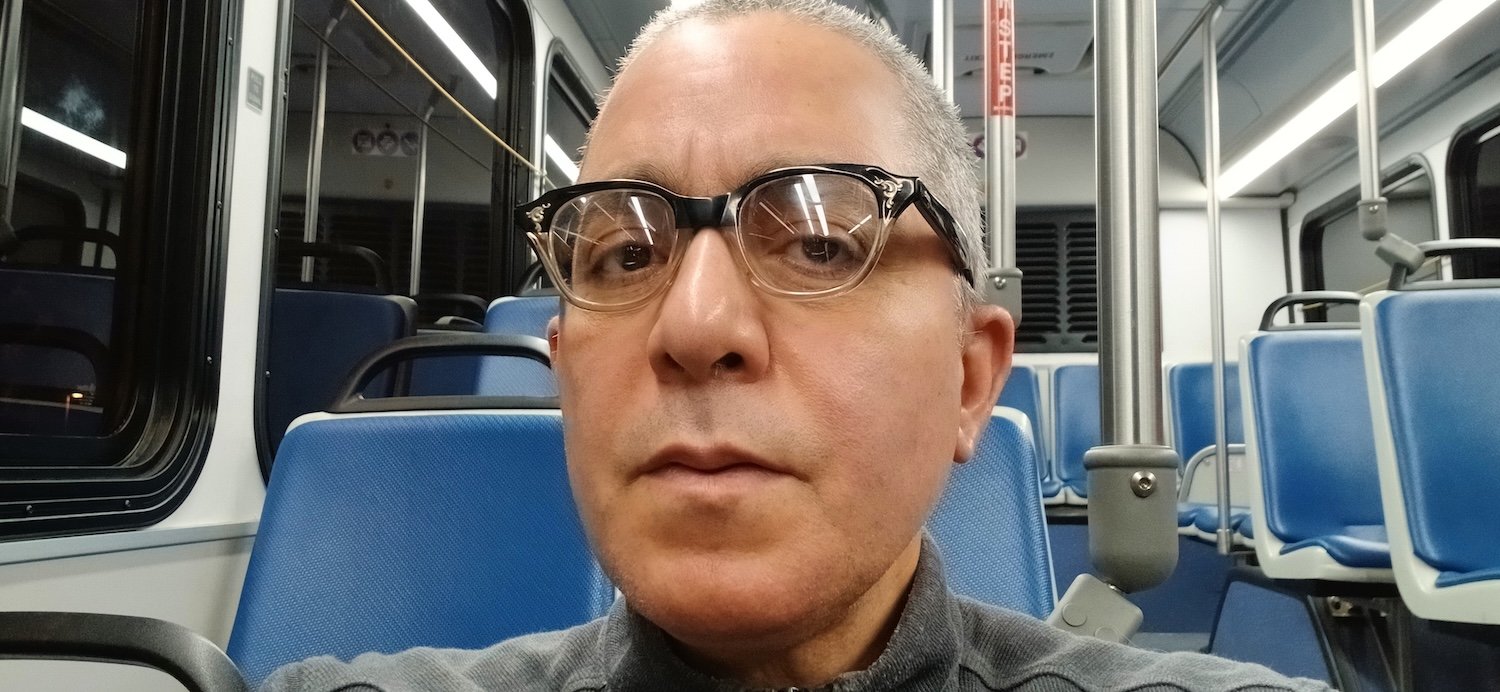

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Morel

Much like all of my journeys, this one too starts in the South Bronx. A walk to the 6 train in Hunts Point at 3:30 AM is followed by a smooth ride to La Guardia Airport on the M60 bus. While in the wee hours the Boogie Down is as quiet as a town in Upstate NY, Harlem is awakening at 4:30 AM. The corner of Lexington Avenue and 125th Street is already bustling with commuters. The air feels great, though, cool and crisp, and I use the opportunity to nourish my lungs. This late or early, however one might look at time, issues of social justice pop up for me. At the Hunts Point station I wait for the train near the presence of two policemen who speak in Spanish with me. I question my complicity with a system I do not support in broad daylight, and deal with the complexities of my tacit alliances with it. In Harlem again, I ask two patrolling officers as to where the bus stop is. I weigh in on privilege looking for cover under safety. If I were a Black presenting man in Harlem or the South Bronx, would I feel at ease approaching men in uniform in the dark of the night, independently of however they might identify racially or culturally? My bags are heavy as they are, so I opt for not adding more to them along the road. These thoughts about policing belong in my head and I do not need to mix them with my clothing and toiletries. Interestingly, the trip I am embarking on does deal, in my opinion, with two hemispheres —left and right—, East and West Coasts, New York and California. I think of these two places within the US geography not as opposite to each other, but as different realms of some kind. One, two. I remind myself of the number of bags with me, yet let any expectations as to my destination reveal themselves as I go. It is cold in New York City and my body warms itself up with visualizations of the Californian High Desert. It works.

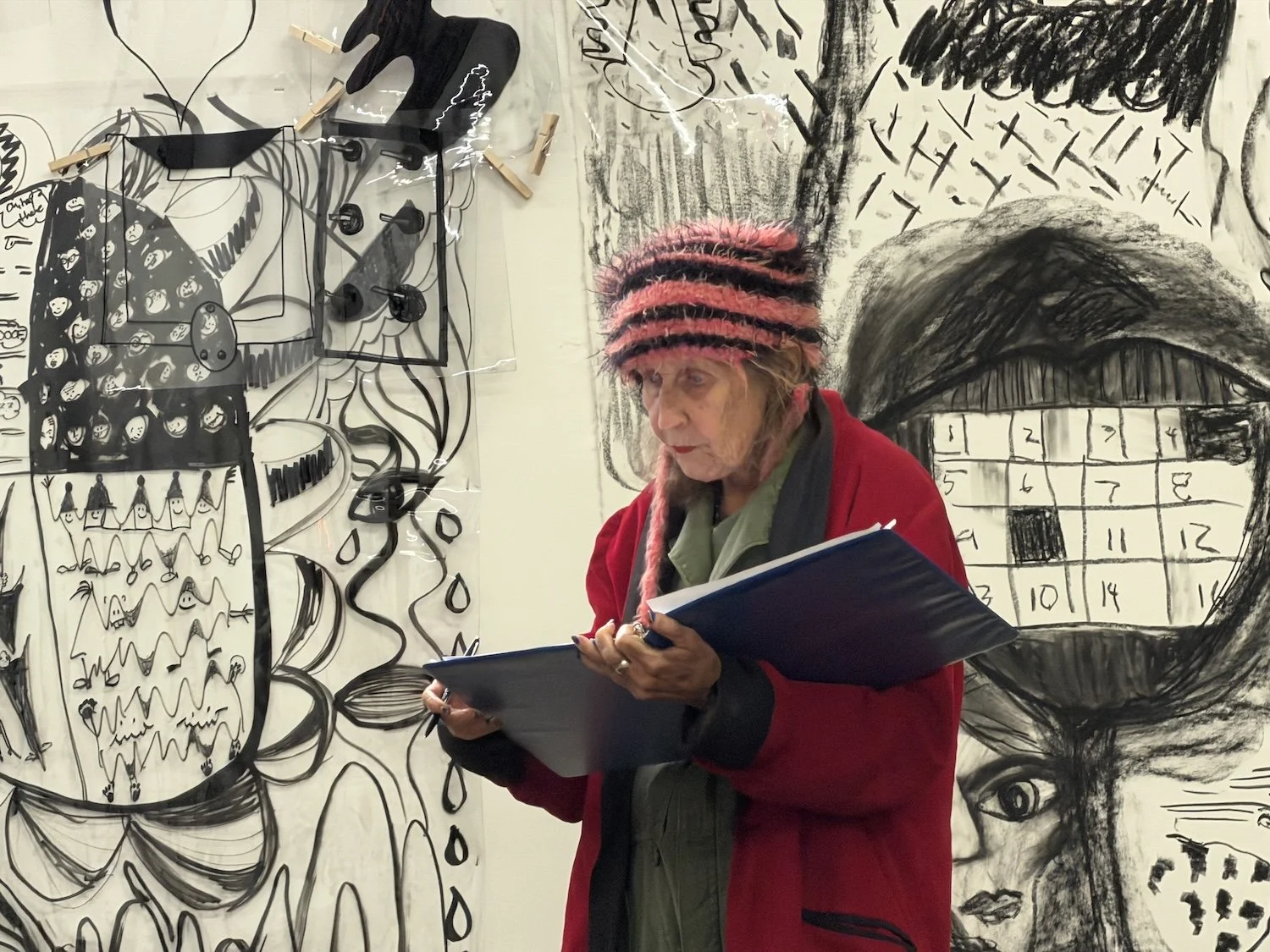

Linda Carmella Sibio and I meet through Martha Wilson, the woman who Linda Mary Montano says knows performance art like no one else. In my search for the roots for performance art during the last 25 years I have made it my purpose to connect with the pillars of this artform, to learn from each one of them and to honor their legacies in whatever modest ways I can or know how to. A first encounter with Linda Sibio takes me in 2019 to Andrew Edlin Gallery in New York’s Bowery. Her exhibition The Economics of Suffering includes programming in the form of one of her Insanity Principle workshops. Martha Wilson is there for this as she is the curator.

An introduction to Linda’s trajectory makes me ponder on the current co-optation of healing by a capitalist Art Industry, where artistic and curatorial statements these days are saturated with terms like ancestors, trauma, grounding, meditation and prayer. I figure the performer in front of me is for real. Linda was diagnosed with schizophrenia while pursuing a BFA at Ohio University. Her practice attest to the hardships she has faced since then, yet also to her intention to be of help to individuals as well as communities across the mental health spectrum. In 2001 she founded Bezerk Productions and with this, Cracked Eggs workshops were born, and found support through a California Mental Health Services Act grant that partners with the San Bernardino County Department of Behavioral Health. I swing between the Artworld of which I have been part, one where decades ago I would hear comments on a panel I was in as to how one specific piece we were judging was too much like therapy; and the other extreme where almost every word that comes out from the institution seems to be peppered with therapy-based language. Because it sounds good, I would say. But Linda Sibio for me inhabits the ground where one does not always have to be grounded, and where concepts like trauma and neurodiversity are indeed genuinely incarnated. Her workshops deploy breathing techniques, which go to address the dissociation, anxiety, and panic, for example, that the bodies she works with might go through. Linda listens carefully to my confession about panic attacks, responding with an insight into the tools that she has been using to face them herself: questioning the fears—speaking with them one-on-one—as to be with what it is without running away from it. It has worked for her.

The evening I set foot in Palm Springs I am overcome by emotions. I consider Palm Trees as relatives, and their sight once I leave the airport floods my heart with tenderness. But how in the world do I get from where I am to Joshua Tree? I call friends who offer to help out, after which I get on my Android to search for public transportation. I find a bus that takes me from Palm Springs to Yucca Valley and I quickly park myself at the station surrounded by mountains capped by snow and the proximity of thorny plants that I begin to befriend as I wait for the bus. One of them teases me to come closer and smell its white flower. I do as instructed, enjoying a gardenia-like perfume. Crows crown my mental space as they circle the wide skies above me. I recall once asking people in Claremont, California, how to move around in public transportation. I could not be guided because none of those I approached had taken a bus before. Perhaps the question from me should have been more direct: “who actually takes busses in California?” I soon understand without actually receiving a response: the worker without a car; the unhoused; the neurodiverse; the unemployed or underemployed; the Latinx maid, gardener or babysitter; the BIPOC clerk at a chain store; those deemed at the bottom of society financially. I imagine that not having a car in most places like California almost amounts to a disability, a societal one, however extreme this might sound and with absolute caution at the moment of making this conjecture. Our bus driver in Palm Springs ventures into the desert in the dark night, with the skills of a nocturnal creature. I trust myself to him and community begins to form in the vehicle. Passengers who know each other greet enthusiastically; or they engage in conversations such as when the upcoming Riders’ Appreciation Day will be. I pay $4.50, a senior fare, for a one-hour ride during which I feel guided with kindness by every single person I ask for directions. The driver drops me off at a highway stop and I soon catch the bus that will finally take me to the Walmart at Yucca Valley, where Linda Sibio and Marzoe, her four-legged companion, will fetch me. All works out and I arrive at my destination.

There is a storm predicted for my first day in Joshua Tree. Many are reluctant to travel because the expectation is that the sandy roads will be flooded; mostly gone with the heavy rains. However, the night preceding the unruly weather there is absolute calm. The exception to this are the windchimes that respond to the strong wind interacting with dunes, prickly beings, and whatever finds refuge under rocks and crevices. An LED lit chandelier hanging from a tree sways back and forth like a lighthouse, offering a point of reference to stranded voyagers. A couple of mannequins let me know that I am entering private property, and a lamp nearby is festooned with delicate cobwebs. I give myself to the silence, letting Linda take me into her abode; a refuge in the midst of a world falling apart. Marzoe thinks of me as an intruder, which I am. At Linda’s I allow my soul a much-needed break. I feel safe, something I have not experienced to this degree in a long time. We sit for vegetarian chili, which my hostess pulls out of her fridge to heat up. At my back, a woodstove keeps us warm and an otherworldly blue light coming from the cellar bathes in mystery the sofa bed allocated to me. I ask Linda if this can be turned off, but that is not possible. Her late husband Blake set this up to go on automatically when the night descends on the desert. I honor Blake’s presence without saying a word. Let the light glow all night. An eye mask will do for me. Any questions about Hieroglyphs and the Insanity Principle, the workshop tomorrow, are let to rest. Darkness mixes together with solitude to bring about the miracle of rest.

Having grown up Catholic, I do not take pilgrimages lightly. Such an endeavor has traditionally demanded some kind of penance. Pilgrimage has been a way to venture out into an unknown world, to atone for misdeeds incurred, a form of punishment and social exile, or a journey to a sacred site with the purpose of regaining health or giving thanks to a higher power. These days the word pilgrimage has entered the Art Industry’s lexicon, a context that can quickly render expressions like this away from their original meaning; to aestheticize them. My pilgrimage to Linda Sibio does not have a religious or even a spiritual component imbued in it, yet many of the strands that inform my journey speak to the essence of walking to a locus of transformation, toward a figure who has been influential to the traveler, and to the quest for restoration. I am reluctant to use the words wholeness and healing because I want to show up at Linda’s class as I am with all of my brokenness. In the past, I have taken pilgrimages to Anna Halprin, and to Linda Mary Montano. Other sites and beings include the Black Virgin of Monserrat in Catalonia; Lourdes in France, La Altagracia in the Dominican Republic; La Guadalupe in Mexico, Chimayó in New Mexico; Medjugorje in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and to an ancient Ceiba tree near Santiago, in the Dominican Republic’s countryside; among many other sites.

In citing the French folklorist Arnold van Genep, Victor and Edith Turner discuss in Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives, how rites of passage are composed of three key elements, or what they call phases. There is the initial detachment of the person or collective when they transition from their customary day-to-day, moving from here to a liminal stage, that of the passenger or the person in transit. As the pilgrim goes through the threshold represented by the liminal, all that is familiar to them gradually becomes ambiguous. To me this is the space of the unknown; that of the shifting ground. Finally, the traveler reaggregate themself as they return to the place of departure. I would highlight that this last phase includes reflection, meaning how the journey has changed perspectives for the person who undertook the road.[1] The path into Linda’s teachings is meant to be non-linear. At the Fire House that has become a cultural center at Joshua Tree we are invited to work with hieroglyphs. This is a trip into the unconscious, fragmentation and into the abyss. Participants are meant to relate to the day-to-day of the unhoused, the “insane” and those seen as living on the fringe. All of this unfolds as we negotiate space with an interruptor, a person that Linda assigns as a counterforce within the flow of activities we are asked to develop in groups. In my case, the challenge is embodied by two people who play down my creative efforts, acting as a hindrance into the road I am seeking to plow through. Maybe not so much nowadays, those in the midst of a pilgrimage have had to wrestle with wind, hunger, wild creatures, robbers, and even with the upkeep of their wellbeing as they traverse uncharted territory and come in close contact with unfamiliar cultures, nations, and diseases. Pilgrimage has been equated to a passage thought life with all of the peaks and valleys.

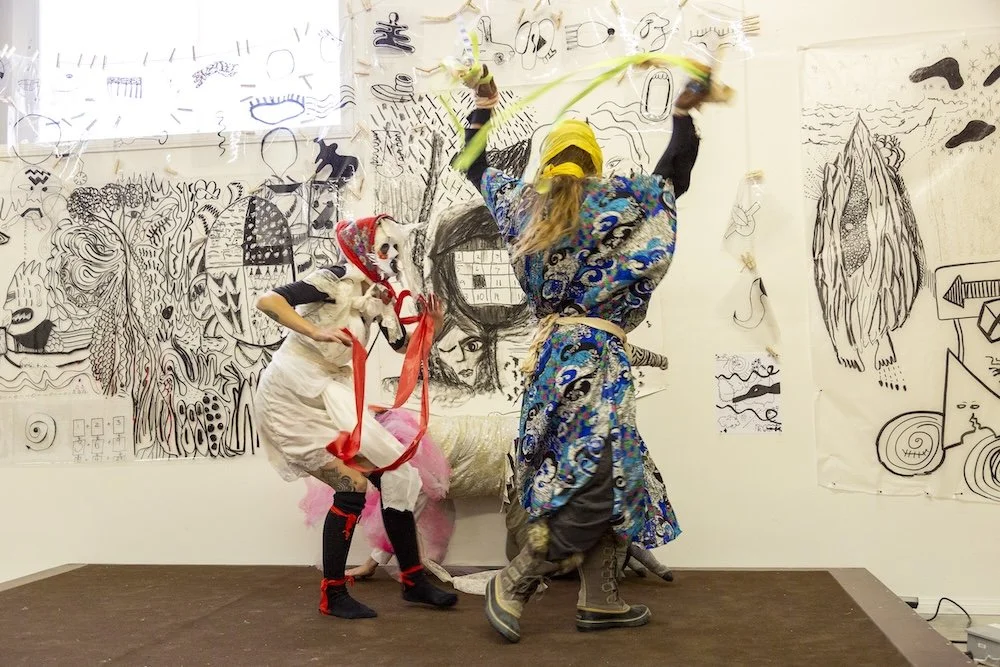

Throughout the first part of the workshop with Linda we move into drawing, writing and generating a five-minute performance art piece integrating emotions, voice, and movement. A couple in our group kisses, eliciting questions about the private versus the public expression of affection. Tension becomes palpable, to which Linda steps into head first. It becomes clear that this is a courageous space. The wind outside is kept at bay by the metal gates offering an entrance to the Fire House. The rain is not as easy to curtail and water starts to seep under a wooden door. In the desert, and in California at large, weather changes can be a serious matter. Inside the Fire House emotions run high as we look to put together solo pieces, so the inside is in continuous dialogue with the outside. The wardrobe that Linda puts into our hands is made up of props that used to belong to her mentor Rachel Rosenthal, the performance art legend I wanted to do a pilgrimage to years ago, but that I did not pursue in time before her death. I settle for a strapless red dress that Linda has in her personal closet. Our group makes masks to match our emotions. Mine is thoroughly wrapped in ribbons. We feast on Japanese curry and white rice as the rain uses the tin roof as a drum. I sit with this creative cacophony in and out, all around.

A home can be more than a shelter, for this reason during my stay with Linda, her casita in the desert is a sanctuary. Hot tea. The crackling wood warming up the space. The blue light bathing the sofa bed. Marzoe dozing off in the front room. Telephone calls arrive, weaving themselves into the quiet enveloping us. It comes to my attention how Linda receives steady support from neighbors, as well as how she serves as an anchor to those in urgent need of help with mental health issues. The network that Linda’s work sets forward is a testament to how to live one’s life as a creative beyond the white walls of the gallery and, for sure, beyond the theorizing of the white tower of academia. The seamless overlap with which Linda moves around life is visible to the eyes and noticeable to the senses. She has been testing her teaching approach with herself when it comes to mental/emotional and trauma-related situations. I therefore am comfortable discussing my panic attacks with her, or hearing her take on how people can address voices they hear but no one else does. She tells me, “You ask someone else in proximity if they too hear what you are hearing. You can also disarm some of the harshest voices telling you to harm yourself by challenging them.” More tea. No sugar. No processed food. We top our salad with olives, cherry tomatoes, and honest conversations. I am in the presence of a wise teacher.

The lack of distractions in the desert makes this the ideal site for the kind of introspection Linda is walking us to. On day two of the workshop, the rain is gone but the cold persists. I am determined to perform a ritual outside, the subject of which—for me— is fear. As I tighten the ribbons around my mask, I hear Dale Borglum, from Living/Dying Project, in my head, reiterating to me how all fear is fear of death. “Am I so caught up in this dimension that I cannot let go? Is the fear deep in my bones, an ancestral one going back to some of my relatives trying to leave Lebanon behind, while their hearts refuse to move forward with the trip?” At the workshop we vocalize emotions, sometimes with shrieking sounds that come from the deepest corner of ourselves. We witness each other’s pain with the unspoken understanding of its oneness. I can’t remember much laughter, but laughter is there as Linda teaches us of the flowing nature of emotions. There is sadness in happiness and anger in sadness. We practice eliciting two seemingly disparate emotions, one emerging from the left side of our bodies and the other from the right side, that is, until in the back and forth these emotions collide, mix and become almost one.

In the process of wearing our masks some identities are surrendered and others come to the foreground. I no longer know who is who. Tonalise, a participant, takes the silk shirt off her back to hand it to me. “It looks good with your dress and it will protect you from the cold,” she says. I immediately feel warmer. Yes, the shirt helps and so does her generosity. Ann Romero de Córdoba and I practice outside. I share with Ann that this is as much of her process as it is mine; to give attention to what is talking with her—through her. Jorge Davies, the other person performing in our small group pairs with Tonalese, a local resident, to become our interruptors. “When the work that you are trying to do is meaningful; when it is meant to suggest upgrades to this reality, you will find some obstacles. Do not let them deter you.” I am reconstructing the words that Susana González-Revilla shared with me weeks back when we took a walk in Riverside Park in Manhattan.[2] There is a difference between letting go and giving up. Linda is an example of this, with her teachings pointing in the direction of positive resistance. Now that I can see all of this in perspective, I picture her as the guide walking each one of us in class through water, fire, wind and down underground—to watch us come back from the other side as she extends a hand to us.

In the hours allocated for our final performances I have no idea of who is who. At times, I become dizzy, lost and utterly confused. I mention this to Ann, with who I am co-performing. I blame it on the dress, on the mask, on the sounds, none of which are really accurate. In the sands of the High Desert, I run into the horizon, just a little bit. I dig a hole deep enough to bury my head and my thoughts. I end up concealing my mask under a mound of sand, overnight, to see if the ground can soak up all or most of my fear and free me up. I prostrate myself on the sand, lifting my dress up to my head knowing that my whole nude body is sacred. In the Fire House, I sit to be with the other performances. The person on stage swinging ribbons that come out of their hands commands my concentration. The audience is invited to interact with the performances with old-fashioned washboards that we scratch with knives, stones and other noise-making items. This becomes part of a balancing act. The sound traveling in both directions. The vocalizations rocking from side to side like a pendulum. The decentralization of the energies. The ways in which the mind, at least mine, is brought to the present with no thought to contend with. That is how our weekend with Linda Carmella Sibio ends, and begins anew, as we leave the space and meander into the dark.

[1].Victor Turner and Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives, 1978 (New York: Columbia University Press), 2.

[2]. Susana González-Revilla, conversation with author, New York, NY, October 20, 2025.

A Pilgrimage to Linda Carmella Sibio / A Travelogue into the California High Desert ©2025 Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful

Special thanks to Edwin Ramoran, Jay, Yolanda, Eva Malhotra, and every single being who was so kind to me during this journey. May each one of you be supported by community.

Linda Carmella Sibio began her career in 1975 while having a loft in Manhattan where she maintained her studio. Notable moments include working in Andy Warhol’s Silkscreen Factory and having prestigious artists such as Al Loving visit her studio for a critique. Sibio made friends with David Diah and went to small gatherings where Frank Stella spoke about his work. During this time she was in several small group shows and was interviewed by the editor of Art Forum magazine. Sibio created many large-scale paintings and drawings where the themes were monsters and garbage (or found objects).

In 1985, Sibio took the bus to Hollywood without a penny in her pocket. From there she worked with such prestigious teachers and artists as Eric Morris, Rachel Rosenthal and John Malpede. At one point she was teaching a workshop in Skid Row called “Los Angeles Poverty Department” (homeless ensemble) and studying and performing with Tim Robbins and his group The Actor’s Gang. A large achievement during this time was an interdisciplinary work called Condo at Thieves corner, which attracted an audience of 2,000 homeless and art seekers.

During the nineties she did solo interdisciplinary works shown at Walker Art Center, with Creative Time and Franklin Furnace, at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions and other venues. She also began getting large grants including several Cultural Affairs grants, The Rockefeller MAP award, and The Lannan Foundation Award. Her pieces were entitled W.Va., Schizophrenic Blues, Azalea Trash, Apartment 409, Hallelujah I’m Dead!, Suicidal Particles and ‘Energy and Light’ and Their Relationship to Suicide. During this period she directed the project “Operation Hammer” and did interdisciplinary works with mentally challenged persons from Skid Row. The issues dealt with included homelessness, mental disparity, prostitution, gang violence, serial homicides and suicide.

From 1997-2001 Sibio started her painting series The Insanity Principle. She moved to the Hi-Desert area of California and performed and directed with a group she developed called The Cracked Eggs. California Arts Council awarded her twice once for her community workshops with the mentally different. Her series the Insanity Principle has toured at the following venues: Andrew Edlin Gallery (representative), The United Nations, The Kennedy Center, The Armory, Track 16, Scope LA, Brussels Art Fair and others. In 2008 she received the international award for the visual arts called Wynn Newhouse Award. Later that same year she had to discontinue The Cracked Eggs project due to the diagnosis of a serious chronic physical illness. It was during the worst period of this illness when she was near death that Sibio designed a show called The Economics of Suffering. This show is about how the economic decline affected the oppressed population and presented at her gallery, Andrew Edlin, in 2019.

In 2015 Sibio received the Emergency Grant from Foundation for Contemporary Arts for her evening that included Human-Pig Hybrid (a performance), and Schizophrenic Brain Trust (visual art show which lasted one month from Jan. 15 – Feb. 15).

Of some note: Sibio received a government grant (from 2010-present) to open an “art business.” Her business is around fashion/textile design. Sibio also does continuing educational workshops on the issues of madness and creativity.

Linda Carmella Sibio related links: website / Andrew Edlin Gallery / Instagram / Facebook

To return to Incantations main menu, click HERE