Jillian McDonald

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo: Jillian, can we start where we left off? If I am not mistaken, that is almost 20 years ago when you were transforming clothing for people, giving tattoos, and also gifting plants. Some of this was happening at Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s exhibition Looking In. We were both part of this experiment as New York City was in the midst of drastic changes. The moneyed wanted back the urban life.

Jillian McDonald: It’s been a long time since we left off, but it’s great to reconnect. This year has been good for reconnecting with friends or revisiting ideas. The LMCC storefront exhibition was partially intended to resuscitate downtown Manhattan commercial properties by attracting passersby to look in the windows, filled with art and performances a few blocks north of the World Trade Center . Street level businesses had been shuttered and vacated after 9/11. I was just out of art school and making artworks that provided services for passersby. From a storefront, I spoke to visitors about their fears and borrowed items of their clothing, embroidering protective messages into the seams. The messages were based on fears about relationships and ruined oceans, failure in school and the newly launched War on Terror. People agreed to leave their clothing with me and come back later to retrieve it. Separately, I propagated houseplants and delivered them to people in their homes. I was curious about trust and how to connect in meaningful ways with strangers, thinking about how friends and neighbours give each other houseplant cuttings, in a gift economy—it also seemed absurd to be delivering tiny plant adoptees all over the city on my bicycle. I also gave heart-shaped “Be Mine” tattoos to strangers in the subway on Valentine’s Day, trying to spread some love with a phrase which is normally exclusive and possessive. Other works not part of the LMCC show included a hair salon where I only shampooed hair, a storefront in which I transformed peoples’ favourite clothing into new articles, and a web-based, non-professional, advice lounge which was also performed live at a few public art festivals. What you identified is happening now again with people wanting back the urban life after drastic change—it’s not just the moneyed and not just in New York.

NDERE: If I may. I will use the word “we” to talk about the energy that a group of us were kindling in the early 2000s: You, María Alós, Rebecca Hermann and Mark Shoffner, LuLu LoLo, Nancy Hwang, Yoko Inoue, and me too! There was something remarkable happening with the arts and the streets that seems to have gotten lost. Can you talk about that time as it pertains to your experiences?

JM: It felt like an optimistic time, and those artists were open to engagement without trying to solve anything. Almost everything has changed in New York since then; in me too—my work had many lifetimes, and it’s hard to remember the enthusiasm of two decades ago; thank you for reminding me about these artists and that time. As I mentioned I was fresh from art school where I struggled with professors who tried to cast performance, conceptual, and new media students as object makers. I sensed that was what was required of me in New York and felt lost. Many of my classmates intended to be famous and I felt like a fish out of water coming from Winnipeg, Canada—where there was no art market. I didn’t know any of the artists my classmates referred to in class and was probably experiencing imposter syndrome, without having that name. I invited a performance artist who I admired to speak at the school and hardly anyone came to the lecture. The group you mentioned were more exciting to me than a lot of the artists I encountered in New York galleries—I found my people in that group and also among a group of video artists making experimental new media art. Making ephemeral work in public spaces and online was motivating. I had no space of my own to make things anyway, and even if I did, I was not well-suited to being alone in a studio all the time. Art found when you least expected it was to me the best kind, and on the streets could be found surprising happenings every day—these encounters together provided motivation. There was of course the constant spectacle that is the city, but mundane experiences flecked with extraordinary sights were endlessly inspiring. An alley trash bag animated with rats and moving like a spasmodic body; a cotton candy purveyor on the subway platform yelling on a phone; a city bus explosion for a film shoot with an audience of neighbourhood Hassidim; a kite flying high on the roof of an apartment building. The streets were like a circus, anything could happen—the waterfronts were undeveloped near where I lived, and there were word-of-mouth experimental events happening in old warehouses, bars, secret projection halls, factory sugar tanks, and tall grasses—where there is now only luxury housing and park developments.

NDERE: Going back to what was happening in the early 2000s, I do not see its equivalent now. Hmmm, perhaps Art in Odd Places is the closest to this. It seems that the conversation shifted and the play and humor is all gone. The focus these days seem to be on changing or fixing what is wrong with the world rather than playing with it as it is and seeing what is possible. Broadly speaking, I find most of this kind of art predictable, didactic, and too dry for my taste. You and those mentioned above, on the other hand, were really in it, all the way through with those we encountered through our artwork. That too seems to be at odds now, where the art experience is more dualistic: them and us, and the artist and the usually marginalized communities where they work. I have gone off on a tangent, but I am trying to get you to recall what did not have a name then. Thank goodness for no names. There was not a term for what we were doing.

JM: It might have been called social practice or relational aesthetics, but I hope not—it’s nearly impossible to fix things for real with art and the gravity with which artists try is not my style. I have no idea how to fix anything, it took me all day to put up one shelf this past weekend. Cliff Eyland, a friend and late Canadian artist, made an unlimited print edition called Thank you for not involving me in your relational art project—I concur, please don’t. I’m reading Bad Environmentalism right now and the author, Nicole Seymour, is getting at this too with environmentalists whose earnestness and reproach is lacking in joy and humour and makes the whole enterprise smack of elitism. I remember Anissa Mack’s Pies for a Passerby, Shawna Dempsey’s and Lorri Millan’s Lesbian National Parks and Services, and Pablo Helguera’s Singing Telegram Show too from the late ’90s and early ’00s. The absurdity and spark of unexpected delightful encounters in that period you’re taking about were magical—are you feeling nostalgic? Suddenly I am—these works hold places of legends in my memory; there are projects I would love to realize, which occupy my thoughts sometimes. I’ll never forget your Passersby Museum and the guardian roles you and María Alós playedl—l I know it caught people by surprise, and they probably didn’t know what to make of the situation and maybe thought about it for a long time after that; the humour was palpable and never overdone. La Papa Móvil too —your gestures and generosity, and humourous spectacle are for me what holds this work in my memory. The artworks that thrill me most have humour embedded in them. And they do still happen, but maybe not in New York quite as much. Cindy Baker’s and Ruth Cuthand’s recent Survivor 2020 in the exhibition Nests for the End of the World comes to mind. They invited museum visitors to make appointments to hang out in a hot tub and consider the end of the world as, among other things, sexy. I generally don’t think my own works need to be funny to anyone but myself. I made video works about celebrities for years, mostly Billy Bob Thornton—inserting myself digitally into scenes from his movies in order to change the stories and suggest a long-term relationship between us—and connecting with his fans via the fan websites. I also inserted myself into scenes with actor Vincent Gallo who then tried to sue me, with no sense of humour whatsoever. Most recently I made A Drink with Nick, inserting myself into a 44-minute Nick Offerman yule log whisky ad in which he sits in front of a crackling fire sipping a drink while staring at the camera and barely moving; I thought he looked lonely so I joined him digitally, after the fact, posting my video for New Year’s Eve in case anyone else felt lonely and wanted company—they could play the video and sit with us, too.

NDERE: With all respect for the title, I see you as an Art Witch, the alchemist, the wise woman, the curious traveler. You gave candies to strangers at a subway station as part of The Love a Commuter Project; you have worked with creatures from the other side and turned yourself into one during a subway ride; your work has a dark/shadow side to it that is worth articulating, since both light and shadow work in tandem to create balance. Would you say more?

JM: You’re giving me far too much credit, I’m not very wise and I do nearly everything the hard way. Candies for Strangers was based on a lifetime fear of taking candies from strangers—and I assumed no one would take candies from me. Surprisingly, almost everyone did, often with a smile or a return gift—or at least that’s how I remember it. The action was absurd but also scary. I wonder if people ate the candies? I don’t make that kind of work anymore, but there are still performative aspects to newer work, and I always love working with strangers and dipping into the dark side. Another body of work which also had its own lifetime was a series of videos and performances with horror themes. I spent years making work with horror fans—including a performative video, Alone Together in the Dark, set in an Arizona desert with 50 actors, and Undead in the Night, a live performance collaboration with Lilith Performance Studio in Malmö, Sweden, in a forest featuring 100 actors in 18 cinematic scenarios. In both cases I worked with primarily actors of all ages and walks of life, many of whom had never acted before and never been in front of a camera. In each of those works, zombies and vampires—who are not enemies and have very separate mythologies—appeared together, creating a showdown and overlapping their stories. There is humour in these works but it’s a very dark humour. I used to hate horror films and I still don’t like a lot of them, but when there is humour in the storytelling, as in The Shining or Get Out there is some relief, even while they hit our basic human fears of being entrapped, devoured, or transformed against our will.

NDERE: What is up with zombies in your work? What is your understanding of these? In the island I come from, The Dominican Republic/Haiti, which is the epicenter of the zombie, at least in this part of the planet, the process is meant to chastise, socially speaking, a member of society who has broken the agreements of the community. In some cases, the process might be executed for more selfish purposes. In the end, it is a wrenching way to ostracize an individual. How do you see the zombie in what you do?

JM: I’ve been making work about zombies, the kind we see in popular movies, since the mid-2000s, when I began considering horror films from a place of not understanding their appeal. I was reading a lot of horror theory and trying to watch the films to understand this. Fans propel the horror film industry and stories are recycled and reconfigured. Film zombies are, as far as I can glean, the most outrageous and terrifying horror creature because the climax of each story is the protagonist transforming into the monster! Our fear of becoming the monster, of “turning,” and more crucially experiencing the abject bodily processes of death while eating our friends, family, and strangers, is an extreme transgression. Little did I know zombies were becoming a huge hit in pop-culture and it happened that my interest in them was piqued around the same time as George Romero’s last films came out and zombies were popping up everywhere—from book launches to yoga studios and weddings—they had a really long moment. There is something hilarious about their clumsiness and appearance, despite the horror. I lived in Williamsburg for 20 years and when I left it was unrecognizable from the place where I became an artist. The former mixed-use neighbourhood was rezoned as residential and condo towers were growing everywhere—the construction was unrelenting and probably still is. Zombies as uncritical consumers is a trope in horror films, and in 2006 I made a performance called Horror Makeup—I put on makeup while riding the L train to Brooklyn, as one does, but turned into a zombie and lurched off the train. I directed a large-scale performance in Toronto, with hundreds of participants, called Zombies in Condoland which was a fake movie set in front of the towering condos that were changing the city skyline. In some zombie movies the social system you’re speaking of is present in the fiction—some members of the community are ostracized and allowed to “turn” into monsters, and in some cases kept captive. My interest is waning—zombies still appear in some of my work, thought they don’t necessarily look like zombies. I’ve also been interested in other horror archetypes—vampires, masked figures, and slashers. I am just now completing the final edit of a video I shot in 2008 in which slashers like Freddy Krueger and Leatherface stalk each other in an empty house with no victims. Shifting away from monstrousness, I’ve worked with volunteer actors for over a decade now making video in landscapes and there’s almost always a bit of humour in there, and sometimes there are no actors and no horror. My latest video, The Dark Season is shot in the Arctic as the polar night approaches. It’s pointing to environmental crisis but I’m kind of just showing that the party is over as clowns drift by, a stain moves across the horizon, and Elsa wanders in the mountains. Santa’s dead and inflatable dragons and sky dancers, like the ones in used car lots—are on the beach and in the mountains—they all seem rather zombie-like. I made a performance for Instagram called Patient Zero, with students and artists in Arizona—who become zombified in ordinary situations—a grocery store customer starts eating the flowers, someone falls off a hotel room bed, a woman lies in a cactus garden, stroking plants vacantly, another person sticks their head in a bush, while another stares at the sky and a at a plane making an arc in the air.

NDERE: Tell me about your plant and root drawings and your relationship with the Earth. This might seem like a sudden shift of subject, but maybe not. Again, you once gave me a Flowering Inch Plant (Tradescantia Zebrina). I no longer have this, yet I recall its presence, so the essence of your action is still growing in me in some ways.

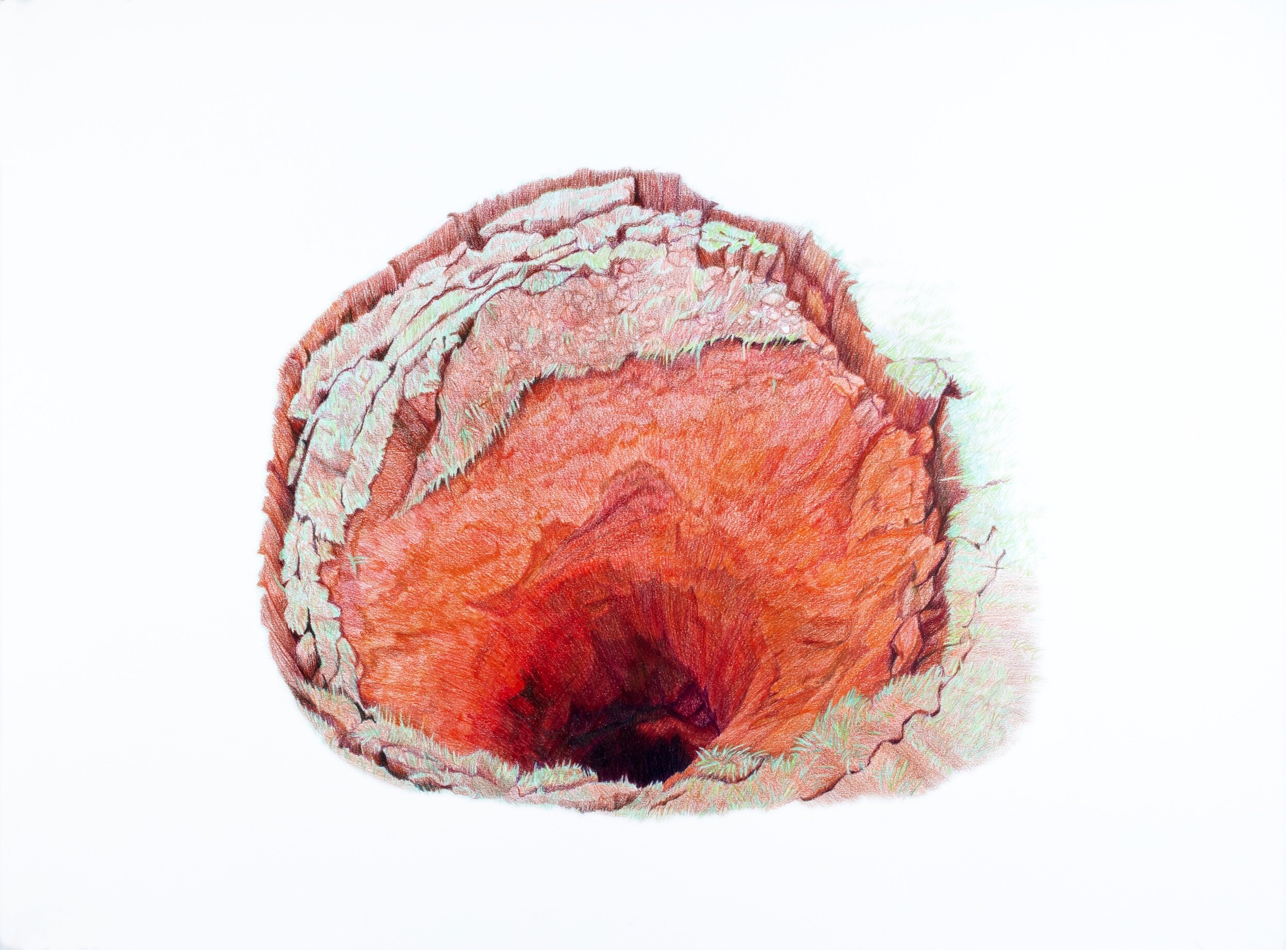

JM: I’ve been drawing holes in the ground and underground roots since spring 2020, when we went into lockdown. A couple of years ago, I dug a hole in my yard for a collaborative performance video with Canadian artist Linda Duvall, who dug a parallel hole on her farmland in rural Saskatchewan; we’ve been developing an exhibition of this work with community workshops about digging. The hole drawings I am making now are portals, tunnels, escapes, and traps—all at the same time. The titles reference the political and psychological states of America during 2020— Deep Sleep, Deep Breath, Deep State, Deep Shit. While I’m drawing, I listen to audiobooks like Underland and Entangled Lives and listen to podcasts about mycology and rewilding. The drawings are labour intensive and at times they were all I could manage in this year. I drew Arctic ice formations also—with the roots and the ice I’m drawing the negative space around the forms—the soil and the sea. I made a video this year called Sweet Spot, a 38-minute series of short scenes where my hands are caressing mosses. In a year when we couldn’t always touch people; it’s an erotic video alternative for human affection. I didn’t own any plants when I delivered houseplants 20 years ago; I didn’t own much of anything. Now I have a lot of plants indoors and out, and I spend a lot of time nurturing them.

NDERE: I see that your garden in Brooklyn and your journeys into the U.S.-American outdoors are something that are coming up for you. Can you elaborate?

JM: I fantasize about calling my own garden a botanical garden because it is, in a way. It’s my first garden, and it’s been life-changing. There is so much to learn about plants and the ground under our feet, so much history, and it’s so easy to screw it up. I am in the garden every day when I’m home—from there I see peregrine falcons, a cardinal nests, a litter of raccoons, stars. I once saw a blood moon through a toy telescope and have hosted children sleeping in tents. I save barrels of leaves that fall from a giant maple tree next door, and compost them in my yard. The tree shade keeps the place cool all summer. When I dug my hole a couple of years ago, I removed all the landfill — bricks, chain link fence, concrete slabs, and garbage that were buried. I appreciate the seasons and I’m out there every day no matter what the weather—the fireflies and junebugs just arrived, joining the garden snails and heavy bumble bees and miraculously no mosquitos. I spend time doing the most mundane things—training moss to grow between stones, cutting the invasive things, and reorganizing ferns and ground cover— it’s amazing to be outdoors in bare feet in Brooklyn. I make small paths from the maple branches and sycamore bark that fall. The ants carry away all the crumbs and squirrels dig for forgotten nuts. There’s a whole world in that yard. I’m also interested in landscape in a larger sense, and the outdoors. Normally, I am making work in northern landscapes and spending loads of time outdoors. I’m planning a video shoot in my yard and a few other locations, including Colorado, later this year.

NDERE: Where are you standing now in regards to art, ideas, healing, motherhood, aging, and what we are going through collectively during the pandemic?

JM: It’s been a long year, frozen in time and space. I’m just getting started on a project that has been on hold since Fall 2020; it feels good to begin but I’m still anxious about travel and being around strangers. I’m happy to be able to socialize post-vaccine and leave my home and take a train but mostly I’m still isolating with my unvaccinated child. We’re alone and far away from family. To be honest, 24/7 child care, remote learning and remote teaching have taken a toll on my spirit, and if everything is really back to normal in the fall I’ll be surprised and on high alert. On the other hand, being a mother teaches me to deal with events that might otherwise seem like major setbacks, to be patient. When de Blasio shut down the schools in March 2020 for one month, I had a feeling it would be at least a year, so I braced myself, and knowing it would be a year made it easier to endure. My kid’s been trained from birth to appreciate alone time, but the ultra-closeness of the pandemic has made us both more dependent, with not a lot of time for reflection. I feel less optimistic when witnessing people refusing to wear masks or treat each other with care, and I see the art world as a very ungenerous place—slowly waking to a history of exclusion. Mothers are one group still left out of a lot of art opportunities—residencies for example. I don’t think much about aging except when I’m sick and this year and a half—since I’m unexposed—I’ve dodged my usual bout of deadly flus and pneumonias.

NDERE: Thank you so much, Jillian for your wisdom. I am joyful to reconnect with you.

JM: Nicolás, thank you for this conversation. I’ve always loved your work, your words and actions, and am happy to learn of your Interior Beauty Salon. Let’s collaborate, maybe gardening in public?

NDERE: Let’s!

Jillian McDonald’s related links: website / Instagram / Facebook

Video links: The Dark Season / Crystal Lake (excerpt) / The Rock and The True Believers (excerpt) / Sweet Spot (excerpt) / Valley of the Deer

Links to drawings: Roots / Holes / Ice

All images above courtesy of Jillian McDonald

Jillian McDonald is a Canadian artist in New York who teaches at Pace University. Solo exhibitions include AxeNéo7 in Québec, the Esker Foundation in Calgary, and Clark Gallery in Montréal. Group shows include FiveMyles in Brooklyn and Root Division in San Francisco. Performances were commissioned by Lilith Performance Studio in Malmö, Sweden and Nuit Blanche in Toronto, Canada.

A CBC Ideas documentary profiles her videos, which were also reviewed in The New York Times and Canadian Art. Critical discussion appears in books like The Transatlantic Zombie by Sarah Lauro and Deconstructing Brad Pitt edited by Christopher Schaberg and Robert Bennett. Awards include a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship, media arts grants from The Canada Council for the Arts, and residencies at Glenfiddich in Scotland and The Arctic Circle in Svalbard.