James Meyer

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles: Here we are, James. We met in 2014 or 15 at El Museo del Barrio when we, at El Museo, were conducting portfolio reviews as part of Office Hours, the year-long experience that I launched for this organization. I am glad that we coincided at El Café and I was able to learn about your work. Would you mind talking about your trajectory in the arts?

James Meyer: I have always been good at making–I grew up just outside of New York City on Long Island and would come to see artwork in new york, I was adopted and my working-class parents have no interest in the arts, this made it possible for me to make art without pressure. I went to art school but was not a very good student. I did not do the assignment but would hand in whatever I was working on, I was eventually asked to leave. At that time in New York, there were new Galleries on the lower east side as SoHo was closed to any kind of painting. The galleries there said that painting was dead and they wouldn't even look at it. Some friends of mine who did graduate from SVA [school of visual arts in New York] had opened a gallery, New Math, and I was showing there and asked them for advice: “who could hire a full-time assistant?” They jokingly gave me a list of names and I went knocking on doors in July and most of the artists left New York in the summer at that time, they still do but not to that extent. The last place, I went to that day was Jasper Johns studio on Houston and Essex an old bank building. The artist Al Taylor opened the door and, as I would come to learn, no one came to the door who wasn’t expected. I handed off my slides and my letter of recommendation and left. When I got home, my girlfriend, now my wife, asked me if I had other copies of my slides and letter. I did not, so I went back the following day to get them back. Upon my return Jasper Johns answered the door with my slides under his arm and I asked for them back. He said that he had not looked at them yet. This started a so sort of argument about getting them back which ended when he said if he looked at them now he could give them back. He hired me and asked me to come back the following day. I became his assistant for 30 years which ended in me getting arrested. That was too abrupt, but I will come back to it. One of my first jobs was to straighten up the FCPA (Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts) art collection, as it was thrown in large piles on the basement floor. They would hire dancers to help and they really didn’t care too much for framed artworks and wanted to get them out of the basement, so they would throw them in piles. The foundation was started by Johns, John Cage and Merce Cunningham, selling donated artworks to raise funds to give away.] As I was picking up artwork I realized that the assistant to the artists would donated work too, but they worked in the style of who they worked for, this made me realize the importance of working in your own style and keeping it. I was there for a very long time and would manage foundry casting and make them. I would work in prints etching, lithography, help make everything: paintings, drawings, drive set up museum exhibitions. At the same time, I showed my own artwork. When I met you I had been arrested and was awaiting trial. An art dealer I had met had groomed me to sell artworks I wasn't supposed to sell and it eventually ended my relationship with Jasper. I was sent to prison and this was very public. I have come to realize that this is my path to take and it was how I had the time to meet you. I had taught drawing classes in prison and I have now finished a drawing class in Maine State Prison. Also, upon my release, I had to start my life over and decided to go back to SVA and complete my degree. I did that, and in my senior year applied to MFA programs and got accepted into the one I'm in currently, and I graduate in May of 2023. All that is a mouth full.

NDEREO: Your work with children at play caught my attention. Can you talk about this? How did you play as a child? How do you play now?

JM: I am very interested in the way that children play. I think it is how they learn to interact with others as adults: waiting to take turns, standing up for yourself, and using your imagination to dream or solve problems. There are several papers written about the importance of play. We moved a lot as a family, and as such, I was always new to the playground. This made me observe others. I was not an adult and I was not part of the play, but I could watch the interactions between the other children. I'm sure I didn't help the situation either, as my brother and I were adopted and we were told very early that we would tell the other children, which at that time I'm sure didn't make any sense to them. I am also 40% indigenous American and we were in middle America, white middle class, so I was not aware that I was different other than being treated differently. Being disentranced from your culture and put in another one, while it gives you lots of opportunities it is also a weird place to be; unmoored. But my wife is a grade school art teacher and I see and work with children when I help her. They are wonderful and I try and tap into the joy and wonder that they bring.

NDEREO: I suggest making a big leap and moving years ahead into your more recent engagement with life and art. We lost touch for a while and I am getting to see, little by little, what you are up to creatively speaking. Can you tell me more about it?

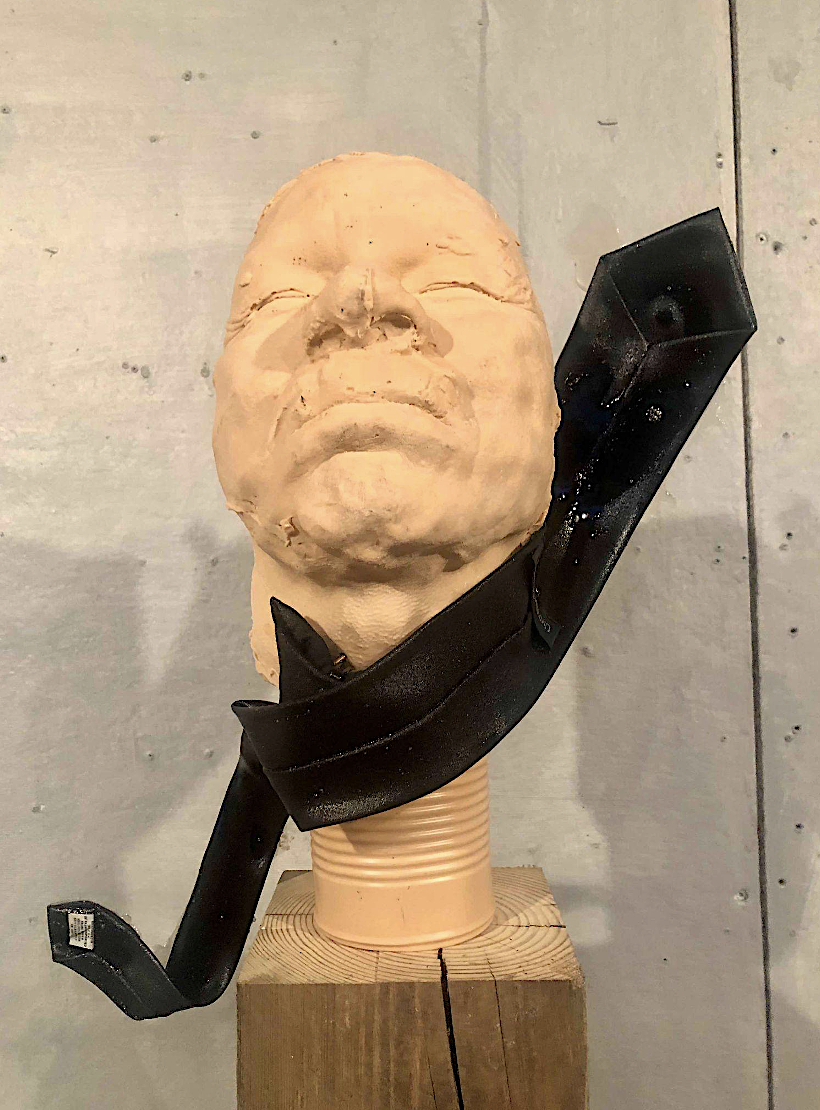

JM: Ha! yes, we lost touch when I went to prison. It was how do you tell someone you just met '“I'm going to go to prison for a couple of years, I'm just waiting to self-surrender.” while I was there, I was welcomed by my community but also not, as I was brought up out of my culture. I am working in a category of art that I am calling “Conceptual Imagery”. Conceptual art uses, expectation, humor, irreverence irony to surprise the viewer. I combine that with the cultural layering of tiles, and images to move the work along. I read the book Blindspot, while I was in prison and it made me realize I inherently defer to white men overall. It lead me on a path to understanding. I made a piece I am very proud of Plaza de la tres Culturas. It uses casts of my face with three different skin tones and three different ties. The expectations of you when you are at work as a servant or in a service role when you are yourself with your culture and when you are trying to fit in. The real plaza in Mexico City is made up of an Aztec building, a Spanish church from the 1500s, and a modern building. It is as if everyone from Mexico is of all three cultures.

NDEREO: How did the drawings dealing with incarceration and the jail industry come about?

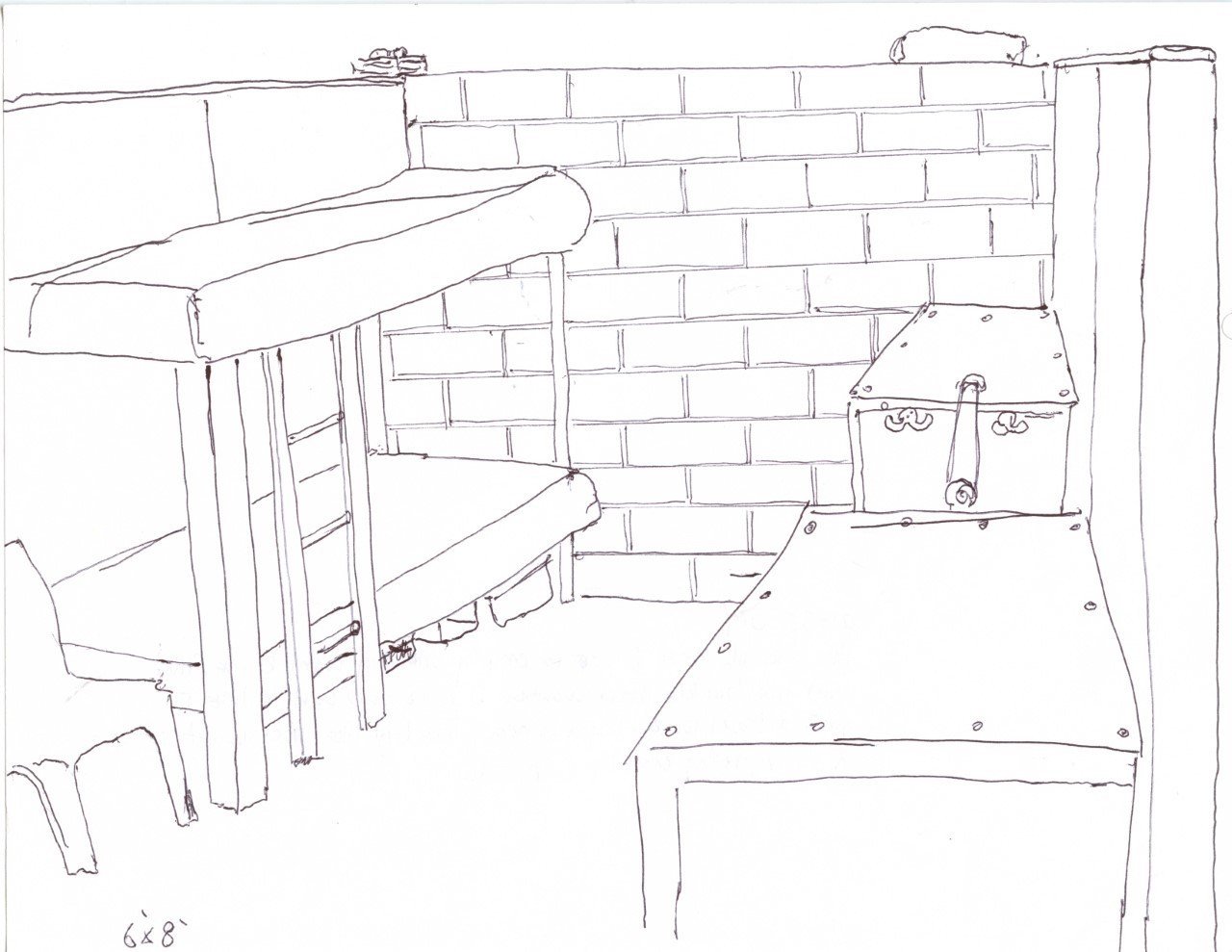

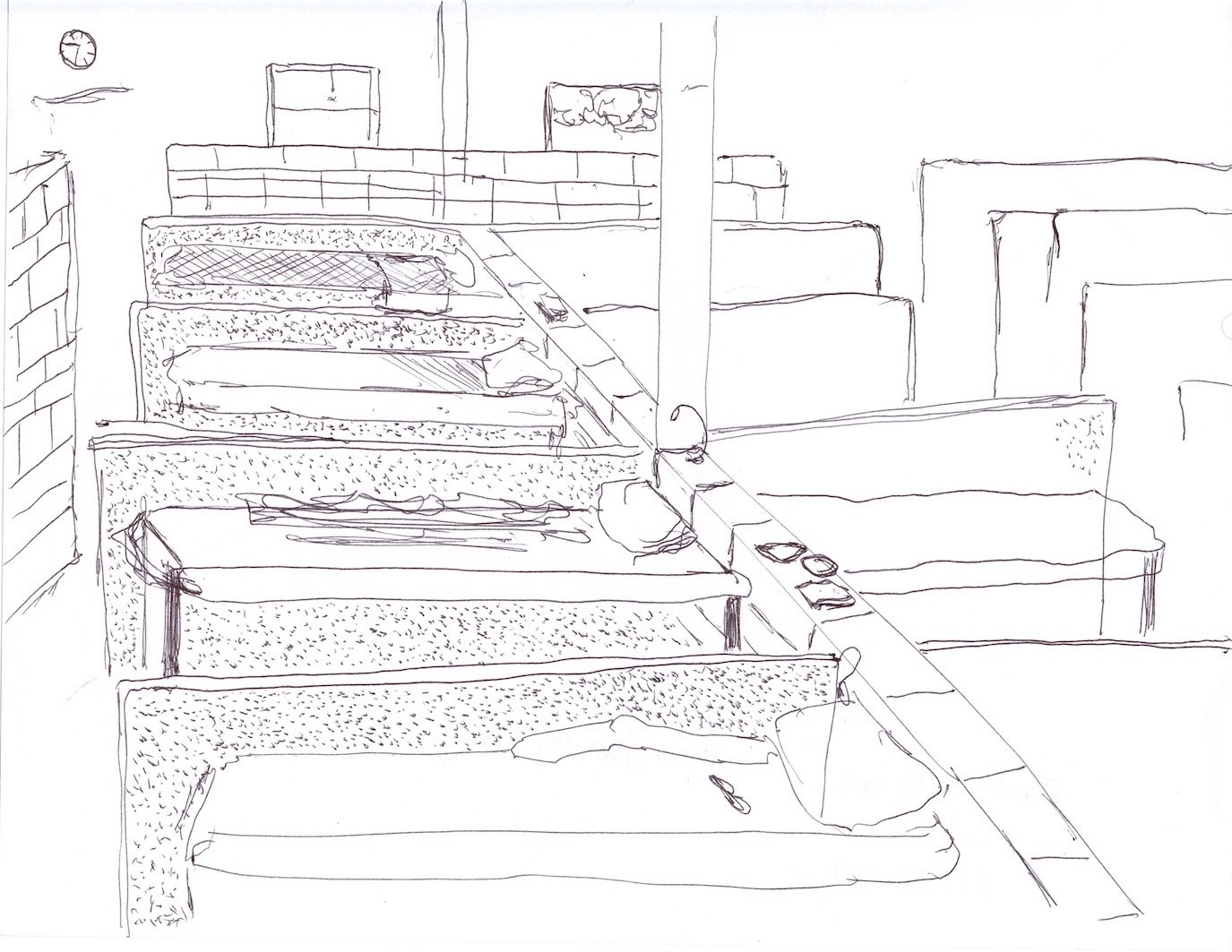

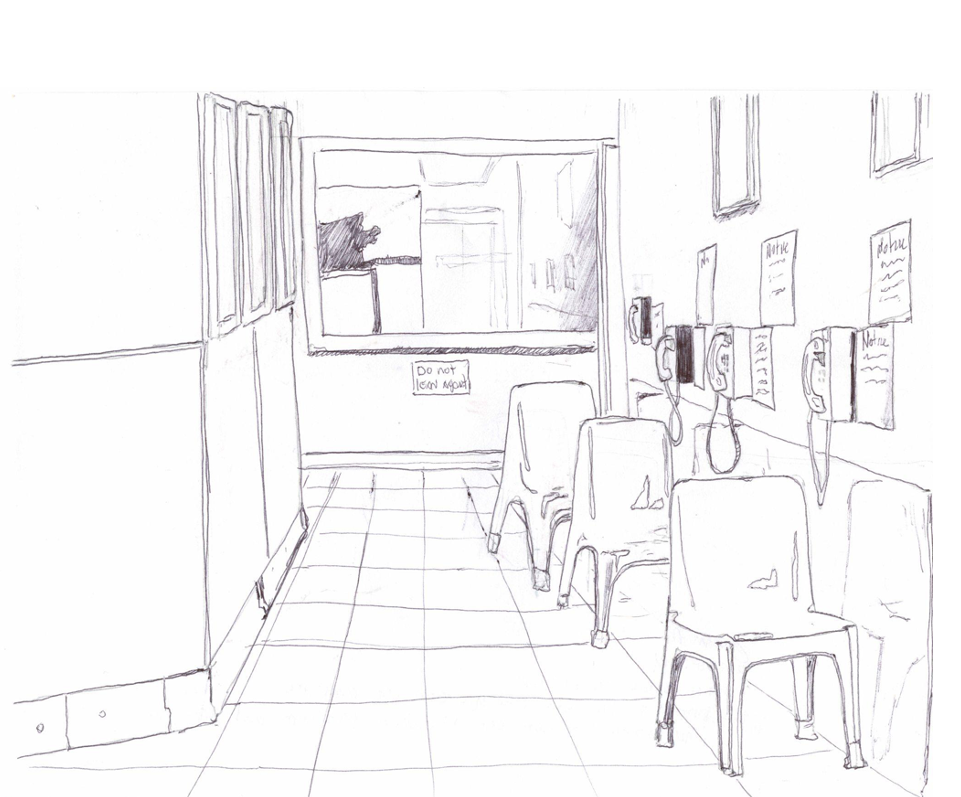

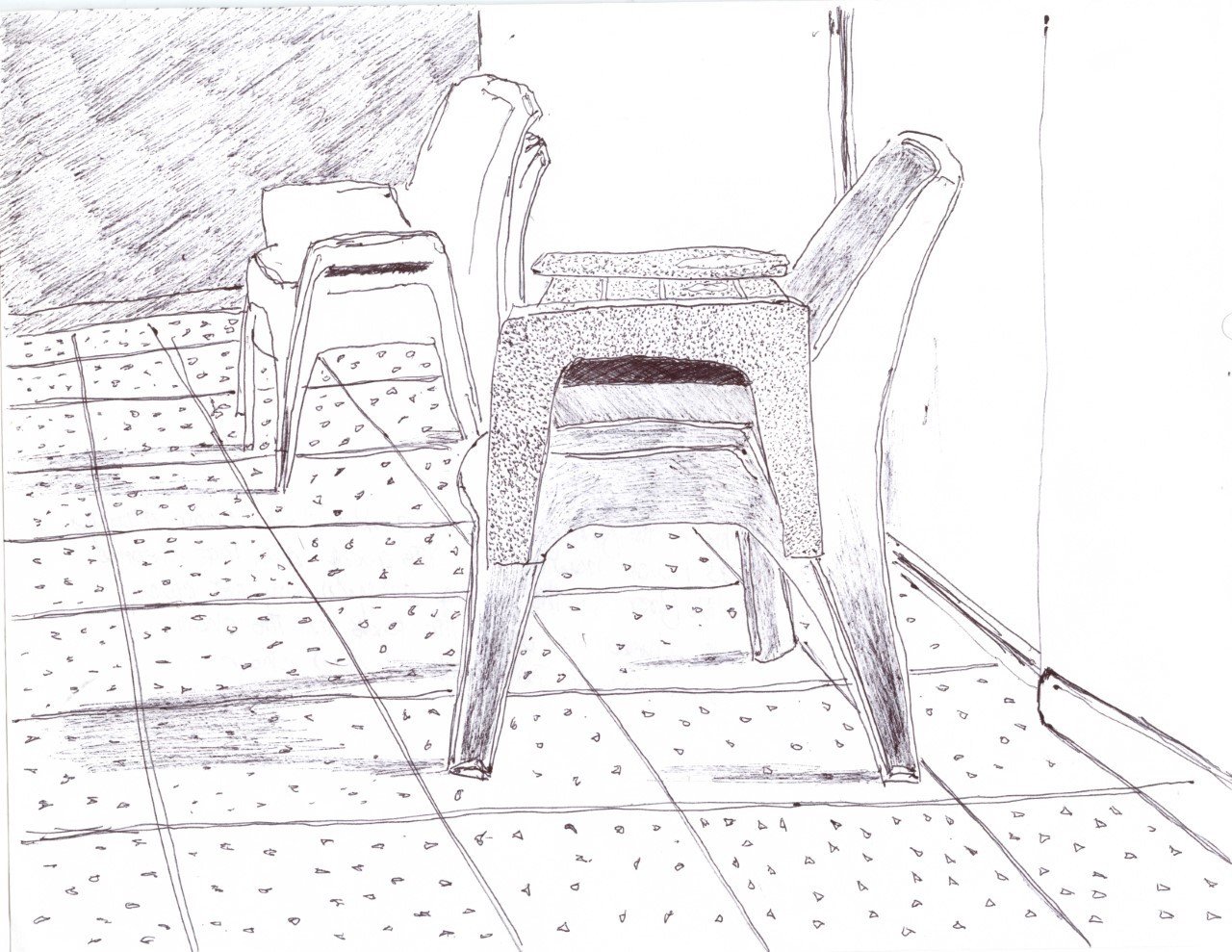

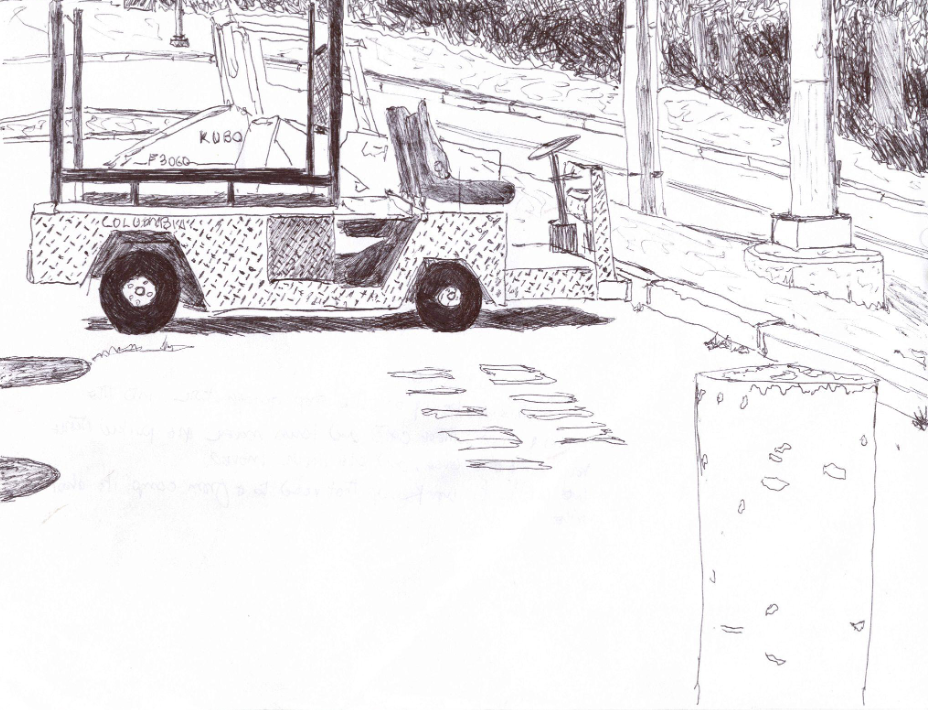

JM: When I was in prison I was not doing well. I did latch on to drawing to keep myself busy, and I drew every day. The guards however would also toss your cell and throw your drawings away, so in an effort to preserve my drawings I would send them home weekly. Being in prison you realize that most people are just trying to get home to their families. Someone I liken it to being locked up at motor vehicles. There are good people but also really annoying people, but mostly just people trying to get home. Because of the catch-22 bureaucracy of prison, in order to get art supplies I had to first take a prison art class–but since no one was teaching the class I was told that I could teach the class and enroll myself so I could order art supplies. When I got home I had to do 500 hours of community service and I was able to do it with a group in NY called Escaping Time. They also let me show some of my drawings from prison. I installed the room floor to ceiling, wall to wall. The room was about the size of a cell, so it was very poignant. I was able to be there every weekend and talk with the visitors. It was great to tell people about the others we had left behind. And what do you want when you send someone to prison? Do you want them punished or do you want them to change and reenter society? Now on the back end of my MFA, I realized I didn't use my studio day that was allotted for me and I proposed that I volunteer at the Maine State Prison and teach drawing classes. I went once a week. I had two classes, one in a low and one in a medium security. They were very proactive and now there is a show of the work in Portland. The work from the drawing classes and other artwork that the guys did. I want to do it every year and go back.

NDEREO: The number of people whom the United States keeps behind bars is growing, and includes a disproportionate number of individuals belonging to BIPOC communities. Being Back and Latina/o/e/x in the U.S. seems like a big problem to the system. I was recently pondering on the phrase from W. E. B. Du Bois as to “how does it feel to be a problem”. There is also the book How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?: Being Young and Arab in America, by Moustafa Bayoumi. I am both Arab and Latino, a double problem, I guess, for “America”. Any thoughts about this statement?

JM: Yes, a lot. Where do you start? I think that things are changing but very slowly. We were recently in Scotland and they had a contemporary art exhibition acknowledging the BIPOC artists from Scotland that were not recognized during their lifetime. There were only about 5-or 6, but it was great. I saw something else like that at the Huntington Library in California going out of its way to understand. PRETENDIANS is an exhibition I have made with two other artists… Ummm…how do I explain this one? I have an ongoing exhibition, a conversation about being indigenous in America, being a sensitive settler. The other artists in this show are Deborah Santoro, Steffay Ojeda, and myself. This is a conversation through artwork, working together on pieces and making pieces responding to the conversation artistically between the three of us. We want to continue this exhibition adding artists as it goes along. We have made a short video and documentation of the artworks. We showed it this summer in Portland but like so many things being shown now, the College did not let the public in as they still had Covid restrictions so we are in the process of creating an online version of it.

NDEREO: You teach people who have been incarcerated. What have you been learning from your students? What can they teach those of us who are supposedly free?

JM: Because I was interested before (I was incarcerated?), there are many things that I learned and continue to be reminded of. One of the frustrating things about life on the outside when you first get in prison is you can’t affect anything on the outside. You can make suggestions but you can't affect anything, so you get used to letting things play out–you get used to not being so caught up in being jealous or what other people are doing because you can't do anything. And it is a very peaceful way to be. Also, every day on the outside is a good day– the sun is up…or it rains… it's all good. Giving back–talking to these guys–who are very appreciative of the time you are giving them. You are using your freedom to come back to prison and make a conscious decision to talk to them. They need permission to have everything: tape, rulers, paper, pencils–all have to be listed on their property. It was interesting how similar the facilities are: run-down; forgotten. One of the guys did show me a way of creating an airbrushed look by smudging out a felt tip pen, which I had never seen before.

NDEREO: So much talk about freedom in the U.S. and in U.S.- American mythology. What does freedom mean to you?

JM: I don't know what do people want when they send someone to prison. There are so many things that follow you out of prison. There are so many things that follow you out the door. When I was first arrested, I got a letter from my homeowner's insurance kicking me off as a risk and I had to scramble and find a new insurance company. I had to get a broker and confide in her what happened so she could help me. My wife could not talk about it without just crying. Then I got asked to leave the bank. I got two checking accounts, one after another closed on me. I had no bank account for a while, as the bank would not take the risk. It is very hard to function with no bank account and no ins. So how do we expect formerly incarcerated people to function in society without these things? They have to resort to predatory means in order to cash paychecks or find ins for cars or homes. When I got home I was managed by a halfway house. They called my home every three hours to make sure I was home. In order to do anything I had to list what I wanted to do a week ahead of time and get approved. If I went on an interview for a job they would call after I left to make sure I went. This meant that the job would know that you were a felon, even though the laws have changed so that you don't have to tell people right away. This meant that you needed to get out in front of it and tell the person interviewing you, so they wouldn't just find out. When the halfway house called first couple times, I said this out loud and I just started crying. Part of what I do when I teach these classes is talking to the guys about the other side, getting home…and that it's going to be alright. At the moment I find the United states like an Orwellian novel and not free– or the false perception of freedom. It is not new. The convenience of the internet and the convenience of our lives online have made it so there is no privacy

NDEREO: What are you working on at this moment? What wakes you up in the mornings?

JM: I am working on my thesis show. I have to write my thesis and make it at the same time. I am reading a book about trauma and the lasting effects and how the mind and body compensate for trauma, and I'm making some conceptual works about that. Ideas have come to me, so I appreciate that. In writing about conceptual art you realize that there is humor or surprise in it as a fire starter. This use of irony is very helpful in making pieces.

NDEREO: I am complete. Thank you so much for talking with me. Thank you for your openness. I so much enjoy your work with children at play and I am looking forward to sharing this with others through this Q&I. I wish you the very best of luck with completing your MFA.

James Meyer is an indigenous artist who worked and showed in New York. In 2015 he was sent to prison and on his return decided to start over and has returned to complete his degree and is currently in graduate school. Working in conceptual imagery, he works through his experience of class, culture, and race to investigate ideas that are overlooked and misunderstood. Meyer works both sculpturally and with works on paper to make installations. His artworks are in the collections of the National Gallery and the Whitney Museum. He is currently working in Northwest Connecticut and, while in School, teaches drawing lessons at Mountain View Correctional Facility in Maine. He has been awarded the commission of three sculptures for McGraw Park in Lewiston Maine to be unveiled this summer.

James Meyer / Related links: Website / IG / email / James Meyer: drawings from Prison (publication)

Images above courtesy of James Meyer