Dora Selva

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles: I first heard of you and your work through Anna Costa e Silva. We then convened at Emerge, the program I co-facilitate online with Marlène Ramírez Cancio. Would you like to introduce yourself and talk about your creative praxis?

Dora Selva: Well, I am a person who was born and lives in Brazil, but has Honduran descent on my father's side. This is a mysterious part of my ancestry–having a completely absent and terrible biological father–, but I feel a deep connection to the Caribbean, beyond South America. I have a degree in body arts and have been intensely dedicated to dance and performance for the last 16 years. I was a member of the Lia Rodrigues dance company in Rio de Janeiro for 5 years, and I always feel it is important to mention this, as it was part of my training, and it laid the foundation for everything that has happened afterwards. I spent a lot of time working as an employed professional with a dancing repertoire, traveling on tour and performing around the world. Having an intense experience like this was important so that I could later dive into my solitary, instinctive and truer creative process. Since I've been traveling, I've known that working with art in Brazil has endless challenge, as opportunities and spaces are scarce, so is getting reviews, agendas, etc. For me, dance is a devotional profession, and I have always seen art as a profession of faith. I understand that it's not a religious perspective, but I have a spiritual relationship with making art. My vital energy depends on it, and so does my balance as a human being.

NDEREO: One key element in what you do as an artist is the pelvis. How did that come to be for you? I see this part of the body being present, honored and reclaimed in the discourse and movement-based work of people like Nina Terra and Priscilla Marrero. What is your very own story as it relates to la pelvis?

DS: Research on the pelvis was a calling in my life, which came at an intense moment of change. I was working in a contemporary dance company with a high workload, and with a lot of physical and emotional demands. I was beginning to understand that, despite being immersed in the artistic milieu, working relationships were extremely mechanistic and, in many ways, colonialist. my body was just a tool, and this situation led me to an unsustainable state of sickness. I was almost forced (by my body) to change jobs and perspectives in all aspects of my life. I had my first contact with pelvic studies through the artist Fannie Sosa, who came to Rio de Janeiro with her Twerkshops. That experience was a key one that literally transformed my way of living and of understanding work, art, dance, spirituality and health. The pelvis is interesting because discussion of it covers very diverse issues: whether political, social, biological, racial or gender-related. I started diving into these waters and offering practices, which at the time were still very similar to Fannie's Twerkshops. Little by little, I built my own method, and after a while Viva Pelve emerged, which is this research project that involves weekly workshops, artistic creations in dance, performance, audiovisual, sound research (in partnership with dj Yas Zyngier), and also content production through social networks.

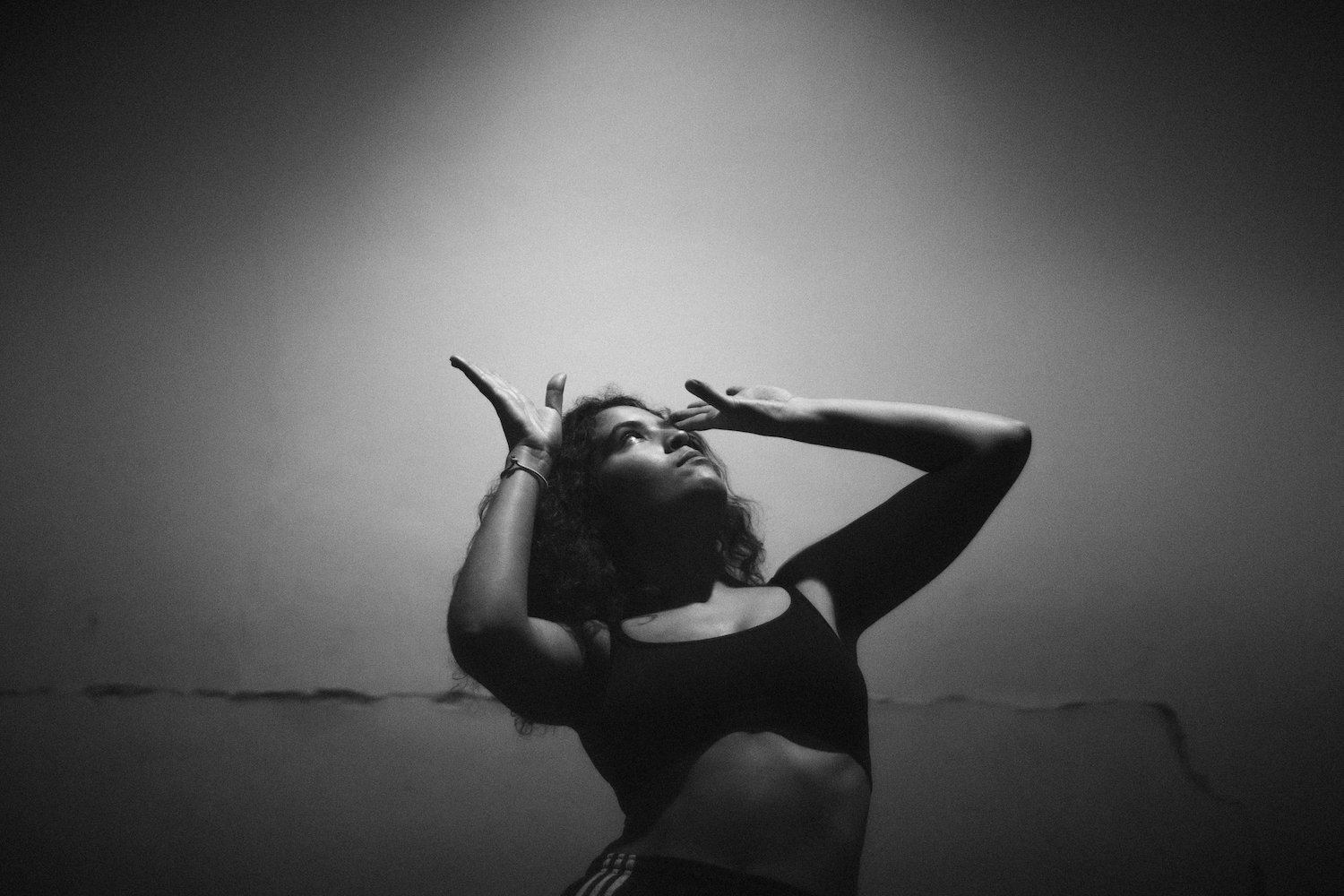

NDEREO: You recently gave birth to a child, and during pregnancy you engaged in a photographic collaboration with Helena Cooper? Can you talk about Dawn, as you called this piece?

DS: This work was very special, because although pregnancy is a maximum period of expression of creativity and fertility, it is a state that is not honored by society. Pregnant women, and then mothers, are put on the sidelines, whether in professional and social relationships, but also physically. Urban centers can be extremely hostile to a pregnant body, and also to a mother and her baby after birth. I say this because it is the experience I am having now and people in general are extremely invasive and disrespectful, at least here. Our desire with Dawn was to go deeper into the image of the pregnant body, both celebrating it and also exploring its dark and obscure aspects. Pregnancy, on the one hand, is marginalized, but on the other hand it is romanticized to the extreme, as if the future mother were an immaculate saint. It is stigmatized by aspects of the more conservative Catholic church. However, the experience of gestating is totally radical, psychedelic, visceral, uncomfortable, maddening and magical. I was in my second trimester of pregnancy, and Helena had her two-month-old baby in the kangaroo. It was an opening for a pregnant woman and a newly-delivered mother to create and express a little of that experience that is birth, the great beginning of everything, within a more real perspective, totally fresh, honest and true.

NDEREO: I recall hearing about a friend of mine talk about how “they were pregnant,” meaning she and her partner were pregnant together–and maybe even her whole family, including her other children. This was a new perspective for me, as I was raised in a world that saw pregnancies only in connection to a female/woman/mother and a child. So much has changed and I am glad about the shifts in paradigms. In the case of my friend, my understanding is that she saw pregnancy as a co-creative collective process, and not as an individual one. What are your thoughts about this?

DS: I totally agree. when a new life is on the way, all roles are changed. We become parents, our parents become grandparents, other children become sisters, cousins, uncles, and godmothers. It definitely takes a village to raise a baby! This is very interesting, and I see that there are two extreme sides. It is true that there is a biological connection between the mother and the baby, as they are in total fusion. Both become a single being divided into two bodies, and there are hormonal, instinctive relationships, which should not be ignored, but the situation in which many mothers find themselves today is one of total isolation, loneliness and overload. It is as if the baby were their sole responsibility, when in fact it is also the responsibility of the community. I feel that our children are not ours, they are of the world. Our body is "just" a channel. It becomes very clear that receiving, creating and caring for a new life is a task that cries out for communion. Anyway, it is the mother's body that miraculously orchestrates the growth of an entire human body inside the womb (!), and this far from basic activity could be more honored, respected and supported, collectively.

NDEREO: Your photographs with Helena Cooper speak to me of the power of the erotic and of eroticism. This can be new a perspective for many when it comes to pregnancy. I am curious to listen to you talk about this.

DS: According to the article "Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power," by Audre Lorde, the erotic is an internal resource, a source of power and information–a force– I believe, linked to our capacity for creation and transformation. This is a force that has been oppressed and devalued both by the patriarchal system and by the practice of colonization (both are very related, in my point of view). As I commented above, it is very common for the pregnant body to be stigmatized in a model of sanctification, and for the mother to even become devoid of sexuality, as she now assumes the role of procreator, home caretaker, and maintainer of the traditional family. According to this discourse perpetuated by the Catholic church, the body considered as female is just a tool for the perpetuation of the species; an inferior body without desires, rights, free will, opinions, and without power. I'm saying this from my perspective as a cisgender woman, as the experience of getting pregnant for a trans person can be very different, with other types of issues. This is why the pelvis is so important, as it is a great portal of connection and returns us to our most intimate truth, and to our power of action in the world. It is linked to the second chakra, that of sexuality/creativity/pleasure. This is important for all bodies, as we are all living in a system that oppresses the body and marginalizes everything that deviates from the norm. But for me, life and sexuality are, in many ways, one and the same. The same energy. Pregnancy was actually a situation of the maximum power of what life is because it is simply taking place inside your body, through yourself. There's the magic too. This state was also the maximum manifestation of the erotic, if we understand it as a force of creation, power, transformation, which is something totally wild and also vital.

NDEREO: There is a tendency Latin/x America, and perhaps beyond this, to think of Brazil as a nation where there are very little taboos about the body. This perception, I think, can verge on stereotypes or false notions of liberation. I am saying this because this is the same progressive Brazil where I saw dictators like Bolsonaro be granted power by many. What are some of your experiences in relationship to the body in Brazil, which is the country where you live.

DS: It is necessary to understand that Brazil is as extensive as a continent, so there are very different bodily experiences between the states, not the east because the climate, temperature and ecosystems are very different in each corner of the territory. It is a great contradiction because there is a Brazil that is exported with images of carnival, beaches, with half-naked people (in general people of color) that sells this stereotype of freedom, while in reality it can be extremely emasculating, racist, transphobic and neo-Nazi. This is a very strange moment, since Bolsonaro, like many dictators, produces a mass effect from a military discourse, completely schizophrenic, as well as criminal. But speaking from the experience of living in Rio de Janeiro, where I currently live, there is a habit of having my body exposed, largely because of the heat (unlike the city of São Paulo, where I was born). I feel that the experience of the body has everything to do with the geographic and climatic characteristics of the territory. In the city of Rio, which was largely and for a long time occupied by the Tupinambá indigenous people, there is a warlike energy, sometimes combative, and also partying. There is a force that is very characteristic of Rio, which also received many enslaved people and which was the port and capital of the country during colonization. For having been colonized by the Portuguese crown, it is a city that also has a feudal and monarchical foundation in its structure. I once saw a documentary about a dancehall in Jamaica where choreographer L'antoinette Stines commented that it was indeed a sexy country. There is obviously a lot of taboo about the body and about the body that dances, that twerks, that feels pleasure and that has the good life as a premise of existence. I feel something similar here, yes, there is a liberation and a possibility of living in harmony with the environment and the physicality, but on the other hand, to the same extent, there are the systems that came with the perverse colonial practices and that demonize and oppress the bodies that depart from the imposed norm (white Christian heteronormative). This has a lot to do with the issue of the erotic that we talked about earlier, since it was common for original societies to has a different relationship with sexuality and consequently with the body (and with the pelvis!), one that was different from the one that was imposed and that became what we can today call western culture.

NDEREO: I would like to hear about dance and movement and I will leave the space open for you to discuss this with absolute freedom.

DS: Well, dance for me has been getting closer and closer to a community experience in its relationship with the invisible world. I feel that when talking about the body and dance there is no way not to mention the issue of colonization, because the massacre that happened in the Americas was decisive for understanding the way we live today and how our original culture was decimated, even though it resisted incessantly. The body is very interesting, because even if it is totally devastated, traumatized and hurt for generations (I see this a lot in the work with the pelvis), our ancestry is simply still there. Human beings, as they are just another living animal on planet Earth, are connected to nature (we are nature), which is a reflection of the cosmos. The macro is in the micro, and vice versa. I commented at the beginning about my connection with the Caribbean, and even here in Brazil, if you come from a mixed family (almost the entire population), it is practically impossible to trace your family tree, as records and memories have been erased by colonial practice. The story of my great-grandmother, for example, is that of an indigenous woman who was raped, and this is the only information that reached my generation. But what I mean by all this is that it is possible to access my ancestry in the most raw and profound way, through the body, and through dance, as they are aspects of the order of the unspeakable and the invisible. The body is life pulsing absolutely and inevitably, so my practices with dance and art have gone towards these dives in the search for this identity and ancestry. This has been the quest of many people recently, and I think this is extremely important for a territory that has been and still is shamelessly exploited by "more developed" countries.

NDEREO: As we close this conversation, is there anything else that you would like to add or say?

DS: To anyone reading this, get up now and move your pelvis! Honor your nature with pleasure and devotion.

NDEREO: I thank you very much for what you do and for allowing me to learn about your creative engagements.

DS: Thank you Nicolás for the opportunity to be here exchanging with you. In talking about us and what we do there is always a possibility of revising and renewing vows with our practice and conduct in the world. This type of exchange has been very important to me, deeper and richer. I often feel a great apartheid within the arts, and obviously a commodification of artistic relations, since we are inserted in the capitalist system... but practices like this are a breath and a great opening for reflection and connection. I thank you!

All images above courtesy of Dora Selva

Dora Selva / links to work and publications: Website / Instagram / VivaPelve website / VivaPelve Instagram

Dora Selva is an interdisciplinary artist of Brazilian and Honduran descent. She moves through the fields of dance, performance, photography and the audiovisual. Her research has the body as its primary material, and is based on the relationships between movement, spirituality, identity and nature. Her research of the solo dance When the waters have grown above the belly of the earth, supported by the residency program of the Choreographic Center of Rio de Janeiro, was performed at several independent cultural centers, between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Dora’s performances and audiovisual works have been part of exhibitions at EAV Parque Lage, Solar dos Abacaxis, Marina da Glória, and Centro Cultural Municipal Hélio Oiticica. She is the creator of Viva Pelve, a research platform focused on the pelvis, its movements, mysteries, power and healing. This project involves workshops, artistic processes, sound research and content creation. Dora is an EmergeNYC alumna.